|

The Believer |

|

|

|

Baltimore City Paper, 2003 |

|

Feature

The Believer

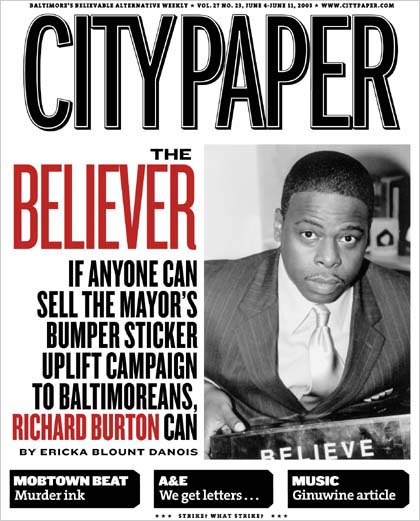

If Anyone Can Sell the Mayor's Bumper Sticker Uplift Campaign to Baltimoreans, Richard Burton Can

A 10-year-old African-American boy walks through the

streets of Baltimore. All around him are signs of the city's

decay. Rotting dirty mattresses lie in alleys, shoes hang from

utility wires. As sirens roar in the background, the boy watches

as a white man holds a plastic tube between his teeth, pulling

it tight around his arm and tapping a syringe expectantly.

"It's everywhere you look. You can't get away from it," the boy says as drug dealers make hand signals to customers. "This guy from the county thinks I'm a drug dealer already," he says as he walks past dope bags being dropped from windows to waiting hands and a woman smoking crack. "I don't want any part of it. But that's who they think I am. That's all they think I'll ever be. "My sister said she's going to the store to get some candy," the boy says as he walks. "I wonder what's taking so long?" "The people of Baltimore are in a fight," a male voice intones. "A fight for the future of the city--a fight that in some places we've been losing. Little by little, one person at a time, one generation after another." Suddenly there are the whirring lights and siren of a police car, open ambulance doors, and a flash of faces--cops, neighborhood folks, and an old man and woman crying. The sirens get closer. There is candy strewn on the ground in front of a vacant store. A little girl lies on the ground. Her two braids look as stiff as a freshly starched shirt, held so neatly in place. Her candy rests safely in her tiny lifeless hand. "Some say, 'It's over. Give up, we've lost,'" the voice continues. "But for the strong ones, the brave ones, this fight is not over. We all know drugs have been killing this community. What will it take to make a stand together and say, 'Enough!'" An old woman slowly lifts her hand and wipes her face with a tissue. The face of the little girl looms closer, her eyes are wide open and impassive in death. This four-minute Believe campaign TV ad only aired eight times in the Baltimore area beginning in April 2002. One-minute versions of the ad aired after the initial, longer ads for 15 weeks between April and August. But a lot of Baltimoreans missed the ads and were left with bumper stickers, T-shirts, trash cans, and banners that urged believe without offering much explanation. As a result, skeptics and cynics abounded, asking just what the Believe campaign is. Who are we supposed to believe in? Ourselves? Baltimore? The eradication of drugs? The campaign was funded by a $2.1 million grant from the Baltimore Police Foundation. But if so many people in Baltimore don't even understand what the campaign is, did the ads work? Are the bumper stickers working? Is anyone believing? "A lot of cities have shook their head and said I could never get away with this," Mayor Martin O'Malley admits while sitting at a huge City Hall table that has been painted with the Believe logo. "We are trying to use it as an antidote to the cynicism that has taken over Baltimore. There is a real culture of failure that exists in Baltimore. I don't know where it is from, but it needs to be eradicated." While the crop of Believe logos that have popped up all over the city since the campaign's roll out indicate that it has appeal for some civic boosters, the cynicism has not gone away--especially in regard to the Believe campaign itself. As this story was going to press on June 3, The Sun reported that Walbrook High School Principal Andrey Bundley and Circuit Court Clerk Frank Conaway, both opponents of O'Malley in this September's Democratic mayoral primary, and the political watchdog group Common Cause Maryland had accused O'Malley of using the TV ads for the new phase of the Believe drive, called Reason to Believe, as de facto campaign ads and an illegal use of charitable funds. O'Malley denied the charge. O'Malley is undoubtedly the man most closely associated with Believe, but he has deputized another man to carry the slogan into Baltimore's streets, schools, and churches. As deputy ombudsman to the mayor, citywide community coordinator of the Mayor's Office of Neighborhoods, and the Believe campaign's field coordinator, Richard Burton, 34, spends much of his time speaking to community groups, youth programs, churches, and other gatherings around the city about just what the Believe campaign is and what it means. And when he shares his own story, as he often does in the process of doing his job, it seems the mayor has found the right man for a difficult job.

Greeting a first-time visitor to his office in City Hall, Burton is as impeccably turned out as a man representing a troubled city should be. His sky blue silk shirt matches his tie, which is decorated with a Believe button. Three corners of a pristinely folded sky blue handkerchief peek out of the breast pocket of his gray suit. He is intense, but he doesn't take himself very seriously as he jokes easily with his colleagues and secretary as he walks past them toward the elevator on his way to lunch. He says he feels he has a testimony, a story, to tell that may help other people in this city. "Three weeks ago my best friend hung himself in prison," Burton says while staring straight ahead, impassioned but struggling to keep his emotions in check as the elevator descends. "He was due for parole in a week and a half. He had written a letter to his son, talking about how he wanted to be a father to him. "Right after that my mother overdosed on heroin," he adds. "Three times last year my mother was in the hospital breathing through a tube. She stayed in a semi-coma for almost two weeks. I have kind of prepared myself for the day she doesn't make it." Turmoil is nothing new to Burton. He was just a baby during the summer of 1968 when rioters threw a Molotov cocktail through the window of his family's home on Gay Street in East Baltimore. The house immediately caught fire, but his grandmother, Clara Burton, ran back in and saved him. Burton credits her with not only his survival but also most of his achievements thereafter. His mother, he says, wasn't around much. Maggie Burton was the fifth of 12 children born to a mother who worked as a domestic and a father who, after he became disabled in a fire, was forced to work odd jobs when they were available. As her family struggled, she was forced to quit school and go to work. By the time she was 16, she found herself pregnant with her first child, Richard. Maggie landed a job as one of the first black female crane operators at Bethlehem Steel and slowly became the primary breadwinner in the family. She worked long hours, getting as much overtime as possible, so she could share her earnings with her family and give her son everything he could ever want. "I thought I was being the perfect mom, but in reality I was an absentee mom," Maggie Burton says with a steady gaze as she sits in the Marble Hill home she shares with her brother and her 15-year-old son, Joseph. "I thought since he had Grandma and all of these relatives that he was getting everything he needed. But I think he would have preferred to have me there than to have all of these material things." But it was when she stopped working at Beth Steel that she really disappeared from Richard's life. Around the time, another brother of hers, who is now deceased, introduced her to sniffing heroin. Soon, feeding her addiction became her sole priority. "My parental role changed with my addiction," Maggie Burton says, her voice raspy with asthma. She wears a Believe T-shirt. "It was like I was the child. Even now it is the same way. He is a leader and ambitious. You won't hear him say, 'I can't do this,' and those are the expectations he puts on other people." By 1987, when Richard Burton was 19, she had gone to a treatment facility in New Mexico for her first rehab stint. But she didn't stay long; the whole time she was there, "all I could think about was getting high," she says now. She quickly caught a bus to California and stayed with a sister who allowed her in the house only under the stipulation that she find a local treatment center and complete the program. She did, and then flew back to celebrate with her family in Baltimore. Within a few hours of leaving BWI Airport, she was scoring heroin again. "I didn't go to treatment for me--I went for Richard," she says, her voice resigned, her eyes sad. "I came right back to the same drug-infested neighborhood and started doing the same thing." It is a problem many addicts in the city face--almost as soon as they walk out of rehab, they become easy prey for drug dealers who are often right around the corner. It is not an issue easily solved with bumper stickers, but Richard Burton thinks he is up to the challenge.

Richard Burton has always wanted to be a star, even as a child. "I always liked singing, acting, playing drums, even though it was the guys that played basketball that got all the girls," he says. When he was 9, Burton could be found looking through the Yellow Pages trying to find ways to get on television. When he turned 10, he finally found his way to break into the business. In 1978, he joined the audience of Hocus Focus, the local ABC affiliate's talk show for young people. With his vibrant personality, he became a guest host on the show in a matter of months. His first true taste of professional success came when the 16-year-old Richard Burton, aka Ricardo, rapped and beatboxed on the 1985 single "Roxanne's Man," one of the many "answer" records spawned by UTFO's hip-hop hit "Roxanne, Roxanne." He later toured with UTFO, Roxanne Shante, the Real Roxanne, and Lisa Lisa. But it was one fateful day, in 1986, while a senior at Walbrook High School that he says foretold "the best years of my life." That day, the West Baltimore school hosted a special guest speaker, Muhammad Ali, and Burton took the opportunity to show off his musical talents to the former heavyweight champ and one of his assistants by singing "The Greatest Love of All" a cappella. Ali was so impressed with Burton that he ended up living with the boxer for three years in Kentucky while working with Ali's assistant, Lee Holmes, on his musical career. "Richard was very persistent when we met him," says Holmes, who has also managed groups like Ready for the World and New Edition, on the phone from Los Angeles. "He was so hot in Baltimore City, when he did tours at the schools, he had to run out of the schools after it was over because the girls would chase him." Burton and the rest of his singing group, dubbed Action Pack, toured and opened for groups like Kool and the Gang and the Temptations, and even sang with a then-little-known Toni Braxton--"when she still had a jheri curl," Burton says. It wasn't until he got a call from home in 1989 informing him that his grandfather died that he decided that it was time to come back to Baltimore. That Action Pack was in the midst of dissolving and had never recorded an album, and that he had hurt his back during a rehearsal, cinched the deal. Not long after Burton came home his grandmother was diagnosed with cancer, and she died in 1994. Since then, he says he has felt like he's been wandering aimlessly without a support system, though he has adopted godmothers and family members throughout the city.

There's something about a walk through Sandtown-Winchester that makes one a bit self-conscious. Maybe it's the brazen stares from guys on the corner, dripping with a combination of rude-boy appeal and man-child insecurity. Or the ashen faces that stare vacuously, indeterminately between life and death. It was here, on North Carrollton Avenue in the spring of 1990, that a young Richard Burton sat on his own stoop with a stocking cap holding his waves in place and his Timberland boots untied in true hip-hop fashion. He had bought the house with residuals from "Roxanne's Man" and money saved while under the stewardship of Ali. As Burton sat daydreaming on the warm afternoon, his reverie was interrupted by the sound of gunfire. On the sidewalk a few houses down from him a young man slumped over. "When I first moved into this neighborhood, I witnessed three murders in one year," Burton remembers as he tells this story while riding in a city-owned Ford Crown Victoria through Sandtown. "I was like, what have I gotten myself into?" Still, Burton has lived in the West Baltimore neighborhood for almost 13 years. He says that his dream "is to make this neighborhood into a little Harlem," pointing to the two- and three-story brick mansions, the carriage houses, and the open parks where jazz concerts take place in the summer. He says it with the conviction of a man who doesn't give up easily. It was the ideals he had for his community and his talent for moving people that would lead to his next career. At a 1995 community meeting in Sandtown, Burton met Maryland political mover Michael Sarbanes (son of U.S. Sen. Paul Sarbanes), who convinced Burton that he had the talent to be a successful community organizer. Soon after, Burton started working with the state Department of Housing and Community Development's Hotspots Homeownership Initiative. The program was designed to decrease crime by increasing stable homeownership through low-interest mortgage loans. Among the tasks Burton undertook were neighborhood safety patrols. "I took that job seriously as a public-safety advocate," Burton says with a laugh. "I would drive around and tell drug dealers to get off the corner. I worked in my own community and I started finding my tires slashed." "He risked his life for this community," says Doni Glover, Burton's neighbor and founder of BmoreNews.com, a Web site devoted to news and happenings in the city. "They were going to try to kill him--his job was to go around and be a snitch." "Richard used to ride around and, where he would see a crowd, he would shine a light on them," Maggie Burton recalls, laughing at her son's fortitude. "I was living with him and his wife at the time, and while he was trying to clean up the area, I was ducking around him trying to find the stuff." With halting honesty, she adds, "The ducking and hiding should have deterred me, but I wanted what I wanted." One night in June 1998, there was supposed to be a Citizens Planning and Housing Association-organized candidates forum at North Avenue and Longwood Street--a notorious drug corner. "We had invited candidates for the mayoral campaign--O'Malley, [A. Robert] Kaufman, all of the candidates," Burton recalls. "It was a night conference, and there were hundreds of people from the community waiting to hear the candidates. No one showed up. "Then I see this white guy walking down the street," Burton says, standing up to imitate a carefree stroll. "It was Martin O'Malley--he was the only one that showed up. We exchanged numbers, and he would call me. I started getting the chance to know him." O'Malley would go on to hire Burton as a community liaison/assistant in 1999, but at first the future mayor's newest supporter got little support from his friends and neighbors for his choice in candidates. "I would wear his campaign T-shirts, and people would turn their nose up," Burton says. "They would be like, 'Why are you supporting him?' "People are so hung up on race, and it is not about that," he says. "Half of the people I met that helped me weren't my color."

"Is this my color?" Burton asks as he holds a bottle of foundation makeup up to his face in a Rite Aid on North Avenue. He has about an hour before he is scheduled to tape the city's public-access cable TV show Eye on Baltimore, and he is in charge of his own makeup. For the past two years, Burton has hosted the hourlong show, which airs on city-run cable-access Channel 21, interviewing Baltimoreans who have done good things for their community (today's taping involves an interview with the owners of the Great Blacks in Wax Museum) as well as celebrities such as Don King, Hasim Rahman, and Lennox Lewis. Just because Burton has become a bureaucrat doesn't mean that he has given up his yen for performing. In the basement of the home he shares with his wife of four years, Crystal, he continues to work on his debut album for MCA Records; he won the recording contract after "Baller," his Curtis-Mayfield-goes-hip-hop single with the Baltimore group Ruff Endz, got national airplay in 2001. He has also taken up acting, winning small parts in the 2000 feature film Animal Factory and the HBO series Oz. He recently graduated to a bigger role. On a cool afternoon Burton sits in his office at City Hall wearing a black Believe jumpsuit. While he answers calls, an assistant from the HBO series The Wire comes to Burton's door and asks him for Believe T-shirts for series creator David Simon and some of the cast members to wear. The irony couldn't be more palpable. Burton is somewhat hesitant to talk about his role on the new season of The Wire as Shamrock, lieutenant/court jester to one of the series' powerful drug dealers, Stringer Bell. His hesitancy comes less from a professional conflict of interest and more from a philosophical one. O'Malley is supportive of his acting career, Burton says, but he is aware of some City Council members' criticism that The Wire's first season contributed to the city's negative image. It is something he says that, as the Believe point man, he has struggled with. The irony continues. In a May 14 editorial in The Sun, former Baltimore City Police detective and The Wire co-writer Ed Burns disparaged the Believe campaign, asking who its audience is: "Is it meant for those last remaining families in those beat-down, boarded-up blocks in our fair city's mean ghettos? . . . Is the message directed at the addict population? . . . Why not send a wake-up call to those who benefit from the systemic failure of unresponsive institutions? That would be novel, it would be listened to and people might even start to believe." From the outset, whether or not it is clear to most residents, the focus of Believe has always been Baltimore's troubles with drugs, city officials say. "Drugs are the single largest problem in the city--85 to 90 percent of the crime in the city is related to drugs," city Health Commissioner Dr. Peter Beilenson says. "We need something to rally around, and the Believe campaign has focused our attention on the drug problem." The campaign's portentous introduction to the Baltimore community certainly seemed to promise a major offensive on the city's woes. It offered a phone number--1-866-BELIEVE--for Baltimoreans to call about various Believe-related concerns, from volunteering to mentor children and getting more information on joining the police force to reporting drug activity and seeking treatment for addiction. But callers to the Believe line were mostly directed to various existing and often already overtaxed city services. Sgt. Sherina Long from the Baltimore Police Department recruitment office says her unit received "several hundred" referrals from the Believe campaign, although she has no statistics on how many became police officers. But callers who phoned in drug activity in their neighborhood were merely referred to the police department. And due to the small number of open beds in drug-treatment facilities, the majority of drug-addicted callers dialing the Believe line for help were referred to Narcotics Anonymous and placed on waiting lists. After spending its $2.1 million grant on the TV ad campaign, and apportioning an additional $100,000 from the Mayor's Office of Neighborhoods budget for bumper stickers, T-shirts, and the like, Believe was out of money. "We did not envision such a strong response and demand," Believe co-chairman Michael Cryor says. "We were caught without the resources we would have wanted to do an extensive ground campaign." But Beilenson says the issue remains numbers. In fiscal year 2002, there were 9,000 treatment slots available to treat 26,000 addicts in Baltimore City. Funding for more drug-treatment slots is easier to obtain when you can establish demand. According to city Health Department statistics, there were 536 calls for drug treatment during April 2001. During April 2002, after the Believe ads began running, there were 1,189 calls. During July 2002, there were 3,053 calls. If the Believe hotline offers no immediate solutions for addicts now, its proponents say, the statistics it generates through the calls that come in may help provide for addicts in the future. In June 2002, after the ads aired and the Believe bumper stickers, banners, and billboards went up, it became Burton's job to try to drive home to the many city residents still mystified or nonplussed by those white letters on that black background the campaign's strangely underpublicized point: that each individual can do something to change the drug problem in Baltimore City. "Initially the drug problem had been termed a police matter, but the mayor realized the only way to wrestle our way out of this problem was to make it a community matter," Cryor says. "Richard had an energy and commitment, we were blessed to have him on staff as we started the Believe campaign. He had an ability to move audiences that typically did not respond." "Having no money to do this, it is necessary to have someone like Richard," O'Malley agrees. "He is a juggler--he is able to do a lot of things--and he has a certain sincerity." Burton now has some reinforcements, in the form of the recently unveiled and already controversial Reason to Believe. This second phase of the Believe campaign is still being run through the mayor's office and it involves more TV ads, this time touting strides the city has made--strides that may or may not be attributable to Believe. But the new phase is to be funded by a coalition of nonprofit charitable foundations led by the Annie E. Casey Foundation. The coalition has raised $21 million for the effort so far and hopes to raise another $9 million. This time, most of the m0ney will go toward more concrete components--after-school programs, drug-treatment facilities, and other programs related to families in crisis and children at risk. Many of the programs that will benefit are already in place in the community. "It doesn't supplant the main campaign," Cryor says. "Reason to Believe is a positive thing that came out of Believe. The foundations decided after the mayor's call to action after the Dawson tragedy that they were doing a number of things individually, but not doing anything collectively." Even as the city's charitable organizations bring their funds to bear, someone still has to serve as a face and a voice for the campaign. Richard Burton still has his work cut out for him.

After Burton speaks to Kids on the Hill, an after-school program in Reservoir Hill, the students are still skeptical. Fifteen-year-old Douglass High School student Ricky Shaw says he believes that Believe is a waste of money. "We have spent all that money for nothing, when we could have spent it on the schools," he says as he runs down a list of things the schools need, including toilet paper, soap, and updated textbooks. Alayne Francis, a 16-year-old student at City College High School, says she still doesn't really understand what the Believe campaign is, and that the campaign is missing young people as an audience: "It seems like it was an effort to stop the drugs and get citizens to call on the drug dealers, but that's not going to work because we already do that, and we get no response from the police." They are not alone in being skeptical about the campaign. Weeks before the objections about the Reason to Believe ads arose, defense attorney Anton Keating, who ran and lost in the city's state's attorney Democratic primary in 2002, started a "Behave" campaign. An anonymous former Chicagoan wrote the following at BaltimoreMustBehave toBelieve.com, the Behave Web site:

On Sunday, my dog and I walked 4 miles along Eastern Avenue. From Bayview, through Greektown and Highlandtown to Patterson Park, Canton and lastly Fells Point. What image did I get? One of DISBELIEF. Trash everywhere. I nearly had to wade through burned out piles of trash on the sidewalk in Greektown. Shoes, hair braids, 1 or 2 needles, beer bottles everywhere of course etc. If Baltimore wants to clean up it's image and attract investors they need to start with a broom.

But O'Malley defends the campaign by saying this is the very sort of cynicism that the city is trying to obliterate with the campaign. And despite all of the campaign's critics, Burton says the money donated for the Believe campaign so far has been well spent. Much like the national campaigns against smoking and drunk driving, he says, the initial intent was to raise awareness both for the addict population and for those profiting from the drug trade. "The first phase of the campaign stirred up questions and got people talking," Burton says. "The next phase will be a whole different campaign." As for the cost, he contends, "It depends on how much you value even just one life--if I spent $100,000 on a campaign and just one person decided to get off drugs and lead a productive life, isn't that worth it?"

When Burton talks hopefully about just one person benefiting from the Believe campaign, it is not hard to imagine that he may be thinking about a member of his own family. "All I really want is for my mother to say she is proud of me," he says. "There are women around the city that say it to me all the time . . . [but] it really hurts. I look for approval from other people." "I am proud of Richard," Maggie Burton says while seated on her couch in her living room, surrounded with Believe paraphernalia. "All of the accomplishments he has, he has done himself. He did everything on his own." The two have been working toward a relationship different from the one they had when her primary focus was getting high and his was keeping her from that goal. Burton clearly remembers some of the harder times. Around seven years ago, his mother was living in his house and, as it turns out, getting high there. "One day I just came home, and I had had enough," he says. "I called the police. I was crying and saying, 'God forgive me.' We went to court, and I told the judge, 'I just want her to go to treatment.' My mother looked at me and I looked at her, and we hugged. And it seemed like the whole courtroom started crying. That day she went to treatment--that was six years ago." For a moment, a flash of pride takes over his smile. "But she left too soon," he continues. "When she came home she looked so good. Her hair was so nice. Her skin was so pretty. But within a week or two she was doing it again." Maggie Burton says her struggle with addiction has continued, and her health has suffered. After being in a coma for nearly two weeks in the summer of 2002, she says, one of the first things that she said when she awoke was that she wanted some help. Previously, about two years ago, she had completed a two-year program, Stop and Surrender, in Philadelphia. She says it was there that she learned about her disease and became committed to fighting it. She says the change that took over her during the program is something that even drug dealers in the area have noticed. "It used to be when they were yelling out their products and I was walking down the street they were directing it at me," she says. "Not anymore." Still, she has struggled with relapses. Maggie Burton says she knows the toll her addiction has taken on her family, particularly Richard. She says she has a good relationship with his young half brother, Joseph, and is able to talk to him about anything, something she senses that Richard envies. "I know it definitely has hurt him," she says, referring to the impact her addiction has had on Richard. "There was a time when we were both so happy." She says now she would not be able to hold down a regular 9-to-5 job because of her health; she is often on a respirator for her asthma and is on a number of prescription medications. But even so, Maggie Burton says her ideal job would be to "help other drug addicts." "I think I have a testimony that would help other people," she says, echoing the very words her son has used, speaking with the same passion.

During his lunch break on a recent afternoon, Burton drops by one of his favorite restaurants, Caribbean Kitchen on Calvert Street, and orders his favorite lunch--jerk chicken, rice, plantains, and corn bread. He finds that the meat is ready to go but the vegetables are still cooking. "How me going to help the mayor run the city and me can't get no nutrition?" he teases co-owner Michael Lewis in a bad imitation of island patois. "You know, I hit these potholes this morning," Lewis comes back at him. "What they doing in the city 'bout these?" "OK, mon, give me the address, and I'll clean it up." "Perring Parkway," the owner says with a wicked laugh. "The whole Perring Parkway?!" Burton asks. "OK, I will work on it for you." Back in his office with his lunch, he is thrilled to find that his proposal for the Believemobile has gone through. The Believemobile, a trailer to be be towed to various neighborhoods by an 18-wheeler truck, will be home to "Mayor O'Malley's Peace in the Streets Tour" and feature local music acts. The Believemobile is one of his dreams, Burton says, and he has work to do to get the financing to make it happen. He hopes it will help keep city kids out of trouble. But before he gets sidetracked, he calls the Department of Public Works about the Perring Parkway pothole situation. "I don't think people realize how valuable Richard is to a city like Baltimore," says David Miller, who has known Burton since elementary school and now works at the Center for Youth Violence at John Hopkins University. "There are so many talented brothers that do the types of things that he does that end up leaving the city." But Burton says he is here to stay. He says he has been blessed to have been able to pursue his dreams in the city he has grown up in and loves. He says, though he has "no interest in being a politician," he wants to continue to do what he has been doing: talking to people, organizing, and getting people to believe in Baltimore--whether it's through his music, his acting, his speeches, or just getting potholes filled. "I have my own agenda here," Burton says. "And that is to help as many people as I can while I am here."

|