|

Ahead of the Curve |

|

|

|

Baltimore City Paper, 2002 |

|

Despite the Sorry State of

Baltimore's Public High Schools, Some Students Make the

Grade

Sam Holden

Donell Trusty

Durryle Brooks

Anastasia Lee

Kareem Branch

Fans whir noisily in the auditorium of Northern

High School on a warm June Friday, but they don't offset

the heat created by closed windows and the hundreds of

bodies packed into the expansive hall for graduation

rehearsal. Sweat pours from numerous foreheads as

students fidget in the rows of wooden seats bolted to

the floor, struggling to hear their names called.

For some, the upcoming ceremony will mark the end of their formal education. Others will go on to college with the same determination that has guided them through a city public-school system rife with staggering attrition rates, school closings, indeterminate restructurings, and a pitiable reputation. Donell Trusty is one of the latter students. He is not at the top of his class--Northern valedictorian Oluwakemi Ajide graduated with a 94 average and will be entering Johns Hopkins University's premed program in September. Trusty's average is only a low B, but that's still an anomaly in a school where poor performance and a who-cares attitude often earn students more respect from their peers than good grades. Trusty, who will be attending the Community College of Baltimore County's Essex campus this fall and hopes to eventually pursue a music degree at the Peabody Institute, is just one of many Northern students who have graduated the moribund Baltimore City Public School System with a college acceptance letter in hand and hopes for a better life. This fall also marks the beginning of the most systematic high-school reform in Baltimore City in more than 30 years, a plan that will cost $55 million over five years and calls for transforming the city's nine neighborhood schools--institutions that draw their enrollment from the general school-age population in surrounding areas, as opposed to the city's three vocational and six selective-enrollment schools--into smaller, more innovative institutions with more difficult curricula, reduced class sizes, and extended school days. "This year's focus will be Southern and Northern," says Mark Smolarz, chief operating officer of the city school system. "In the next few years we'll be working on Lake Clifton/Eastern and Southwestern. They are [also] trying to open a downtown high school--trying to combine [programs currently at] Southwestern and Lake Clifton and bring them downtown." In addition to state and city funds, Baltimore and its school system have already received more than $20 million from private donors toward the effort, including $12 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The Gates Foundation has provided funding to some of the nation's poorest performing school districts, but it initially passed on Baltimore because of its dismal school- reform track record. "We want to make sure [school systems] have a strong commitment to reform," Gates Foundation spokesperson Carol Rava explains, because the foundation's funding "is never enough to fund reform by itself." The foundation got on board in October 2001 after reviewing city schools CEO Carmen Russo's revised "Blueprint for Baltimore's Neighborhood High Schools." "It is a great testament if we hear a leader is planning to move forward," Rava says. The reform initiative offers new hope for students at overcrowded, often violent neighborhood schools, where 71 percent of students drop out between ninth and 12th grades and only 40 percent of graduates plan go on to college. (At selective-admission public high school Baltimore City College, on the other hand,98 percent of graduates go on to four-year colleges.) "Reforms are long overdue because the children are coming out of [high] school not able to read at the sixth-grade level," says Theresa Jones, public policy and outreach director for Families Involved Together, a nonprofit organization that is working to make sure parents, students, and other community members are involved at every level of the current reform. "[The schools] don't have advanced classes, they don't prepare [students] for the SATs." Furthermore, Jones says, "we want to make sure these changes actually happen--this happened before where money went to the administration and not to help the children. We want to make sure changes take place and that they are lasting changes." The imminent reform plan may offer administrators, teachers, students, and parents a longed-for miracle cure for the city's ailing school system. But whether or not the city's worst high schools improve, students like Trusty will navigate the formidable obstacles placed in their path en route to college, as they have every year.

Donell The grass in the courtyard in front of Northern High School is an obstacle course of empty whiskey bottles, beer cans, and Styrofoam food containers. In the last few weeks before graduation, however, most the senior class is floating, high on the idea of getting out. "Daphne, you are graduating by the skin of your teeth--you best be in here," a teacher calls out to a student chatting with friends. Otherwise, the hallways echo with excited banter of proms, parties, and summer plans as seniors and underclassmen alike lounge, play fight, or just hang out. Donell Trusty has found his niche here. Unlike many academically talented students, he doesn't get teased about being studious. He attributes this to his intimidating 6-foot-4 frame, easygoing personality, and a maturity and demeanor beyond his 17 years. Only his innocent face, with cheeks still babyish enough to pinch, gives away his actual age. That and the fact that he answers every other sentence with, "Yes, ma'am." He gives off an air of confidence that's contagious. Trusty comes by that confidence honestly. Without any formal training, he picked up an instrument for the first time in a music class at Northern when he was 15 years old. Two years later, he is skilled in the trombone, trumpet, tuba, and the baritone horn. He has some success with his music outside of school, playing with local gospel artist R.J. Washington and traveling to perform in churches in Philadelphia and the renowned Rev. Hezekiah Walker's church in Brooklyn, N.Y. Trusty, like other students at Northern, has had to make the best of a bad situation. "My son has never read Julius Caesar or A Midsummer Night's Dream--he will have to take a remedial English class in college," says Sonji Douglass, Trusty's mother. "He did do well at the school, but he could have done a lot better. "I am just thankful to God my child made it out of that school safe," she continues. "From year to year, he was getting the same classes--[school administrators] weren't checking the students' schedules. By 11th grade they did not have many of his credits in his school records. By 12th grade his classes were still not reflected." Douglass says things got so bad that she made almost weekly visits to Northern to make sure everything was on track. "I think they were scared of the kids," she says. "By the time I finished with that administration, they should have been scared of me." On an oppressively hot Sunday a few weeks later in mid-July, an auditorium at Coppin State College is bursting with energy. This is where charismatic pastor Jamal Bryant leads the Empowerment Temple AME's services every week. The extravagant outfits and women's hats are conspicuously absent among the congregation this day, however. There are some sharp dressers sprinkled about, but everyone else seems to have come as-is. As the voices of the gospel choir melt together into a hypnotic force and the band picks up momentum, grandmothers, teenagers, young adults, and toddlers alike dance and clap enthusiastically. Trusty stands in front of the stage, clinging to his trombone with a hand bandaged from a recent car accident. He's wearing baggy jeans, a white T-shirt, and white Nikes, but he is serious in his carriage. A neat, thin beard caresses his face, and his haircut is clean. He has been here since 6:45 a.m. and will play his trombone for all three services, the last of which ends mid-afternoon. Trusty's hectic schedule means he doesn't have time to get into trouble. During school, he worked weeknights as a cook at Dougherty's Pub in Mount Vernon; an understanding boss allowed him to do his homework during downtime. Trusty goes to Bible study Tuesday evenings and choir rehearsal Saturdays. His Sundays are booked with church services. Although a talented musician, he isn't interested in playing in the clubs for money. He is content, for now, to hone his craft in church. "My support has come from my mother and my sister's father," Trusty says. "I refuse to allow myself to get caught up in negative activities." He says that while his school has provided little support, it did provide him with the motivation to try to do well. He took a personal inventory of his life while sweating through a summer session at Northern. "In the ninth grade I chose to not do what I was supposed to do," he says. "I decided to follow the crowd and not go to class, and I found myself in summer school that summer. But sitting in that hot summer school made me know I wasn't going back."

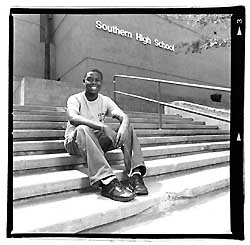

Durryle It's almost time for final exams at Southern High School, and Spanish teacher Vickie Wolverton conducts a review session. Feisty, middle-aged Wolverton orchestrates a vocabulary translation exercise. The class participates by responding swiftly to her questions in unison, but the kids are having fun too. "Soap powder?" Wolverton asks. "El detergente," the class responds. "That was very weak, pay attention. Hygiene paper?" "That's what you use to wipe your butt," a young lady responds through giggles. "We don't need that much information," Wolverton answers good-naturedly. She glances over quickly at one student and says, "Durryle, you have to participate too," before resuming the lesson. When the vocabulary lesson ends, Wolverton sits at her desk and plays the song "Macarena" on a tape recorder while her students silently review for finals. Durryle Brooks smiles easily. "If you're looking for a good story, you should interview our journalism teacher," Brooks says, leaning across his desk. "Our newspaper was censored when students wrote what they really thought about the school." Chatting with Brooks, it's easy to forget he's just a 18-year-old kid. There's no sign of the normal gulf that separates teenagers from grownups. He is as comfortable in a conversation with an adult as he is with normal adolescent preoccupations. He says he is close with a lot of his teachers and has better relationships with them than most of his fellow students. With his straight white teeth, neat haircut, and striped sweater buttoned to his Adam's apple, Brooks looks like any parent's dream child. He reveals that he gets teased by his fellow students all the time for wearing his shirts buttoned all the way up and doing well academically. "They don't like the way I dress, they don't like the way I talk," Brooks says. "They think I think I am all that because I do my work and don't give them the answers." He seems unfazed while recalling the taunting, laughing easily. "A lot of the students here are concerned with the now--girlfriends, boyfriends, clothes, who they are friends with," he continues. "They are not thinking about the future." "The curriculum here is flimsy, it is not as challenging as I wanted it to be," says Brooks, who ended his years at Southern with an 87 average and will be attending St. Mary's College in the fall. While his English classes were challenging, he says he would have liked to take Advanced Placement courses Southern didn't offer. Brooks says he knew everything taught in his business class already, and that one science teacher was talented but had trouble translating concepts into lessons students could understand. More than just an excellent student, Wolverton says Brooks is one of the most mature and thoughtful kids in her class. Talking to him, it is soon clear what led to his maturity. In his Cherry Hill neighborhood, Brooks was a homebody, preferring television to hanging out in the streets. That wasn't an easy thing to do in his house. His aunt--with whom he lived along with two cousins--didn't like kids to run in and out all day, so she locked them outside until dinnertime. He and his cousins slept on mattresses on the floor, but it was still better than what he had become used to. Brooks had lived with several of his aunts on and off since elementary school. His mother, a heroin addict, was in and out of jail and wasn't available to care for him. "I didn't really know where my mother was," he recalls. "I couldn't find her most of the time." When he was about 7, he moved in with his father, also an addict. His dad made no secret of his predilections and often got high at home. Brooks moved out after about five months. By the time Brooks was in the eighth grade, he had moved in and out of several more households, staying with various family friends and relatives. His grades and behavior in class were poor, earning him a spot in Southern's program for at-risk students. It was that year his mother decided to go straight. "I was very proud of her for that," Brooks says, his eyes involuntarily filling with tears. "She didn't go to rehab or [Narcotics Anonymous] meetings. She just cut off key people." He lives with his mother now and says that while she got clean he became born again. He now goes to the AME Hemingway Temple in Cherry Hill five days a week; weekdays after school, he worked as a secretary for a United Methodist Church office downtown. "I have been blessed with a certain mind-set that I don't want to do what the average man will do," Brooks says. "I saw beyond my situation. I am always trying to do something positive." He acknowledges that, even with his self-discipline, there are days when he considers trying drugs. But Brooks says he has a good group of friends who steer him clear. Besides, he notes, his grandmother wrote an anti-drug pledge in a Bible she gave him when he was 3. "I signed it," he says. In September, Brooks' alma mater will be joined by the adjacent Digital Harbor High, which will be divided into four academies, each focusing on a different technology sector. Tenth, 11th, and 12th graders will still attend the old Southern. Digital Harbor will draw its enrollment from interested 9th graders within Southern's enrollment area as well as the rest of the city. Each student at Digital Harbor will be given a laptop computer and access to the schools' state-of-the-art laboratories. Meanwhile, students at Southern will still struggle with outdated and too few textbooks, meager supplies, and decrepit conditions. This past February students voiced their opinions on these concerns in an edition of Southern's school newspaper, The Bulldog. The paper was shut down by Principal Thomas Stephens, who demanded his permission to publish future issues. At the end of school year, journalism teacher and newspaper adviser Tara Williams' contract was not renewed. While there was a great deal of media coverage surrounding Williams' firing, little of it focused on why that issue of The Bulldog proved so controversial. "They are making the new ninth graders think that they're better [than] us because they will have a better school with all the supplies that they will need and the building will be in better condition than ours," student Kenya Johnson wrote in the paper. "[T]he current students should be given an opportunity to get into the [new] school so that we can be treated the same way," student Corey Davis agreed in the same article.

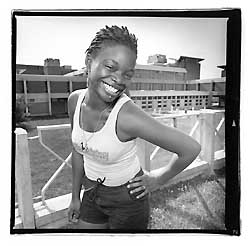

Anastasia It rained most of the night. It was just about more than any girl could handle after getting a fresh hairdo and donning a $400 dress for her prom. Anastasia Lee's brother dropped her off at Martin's Eastwind on Pulaski Highway in a Nissan Maxima with tinted windows. She says the tint came in handy because "I didn't want anyone to see how extravagant I was." The prom itself was anticlimactic, like most special events--the real fun was getting dressed up. And after getting pictures taken and eating and drinking jumbo shrimp, crab cakes, and virgin daiquiris, Lee's night out ended at 1 a.m. Lee's teachers, friends, and even the security personnel at her school, Lake Clifton/Eastern High, all chipped in to help her pay for her prom. One teacher gave her money to get her hair done up in short twists. Money for the turquoise dress with the slit thigh came from the security guards. Her girlfriend's mother did her makeup. At home in Park Heights, Lee sits comfortably in a purple robe adorned with teddy bears and talks candidly. She has been staying with her girlfriend, Moushira Carter, and Carter's mother, Sharlyne Thomas, in their home for two years now. Pictures of Bob Marley and Harriet Tubman line the walls, and Kwanzaa candles sit on the mantle in the corner. The coffee table serves as a showcase of Lee's achievements: certificates for her accounting major from Lake Clifton and her high-school diploma. Lee graduated from Lake Clifton with a 3.4 grade-point average, but before she landed there in the ninth grade she had been kicked out of "almost every Baltimore public middle school." Even at such a young age, supporting herself financially was a priority over homework. "My father wasn't around, my mother wasn't around," she explains. At age 10, Lee started running drugs for dealers in her Park Heights neighborhood, and eventually learned how to cook cocaine herself. "I figured I was too young, no one was going to hire me [for a job]," she says. Around this time, Lee got a first-hand glimpse of drugs' deadly consequences. She came home one afternoon to see her mother suffering an overdose surrounded by paramedics and neighbors. "She passed out in the house and was gasping for air and asking for water. . . . I didn't know what to do," she says. Her mother survived and now lives in a senior assisted-living center. Lee hasn't lived with her mother in more than six years. She later moved in with her father, who is disabled and also addicted to crack, but that didn't work out either. She went into the foster-care system before landing with her godmother, Jacqueline Hicks-Reed, in Parkside. That was when her grades in school started turning around. "Sometimes I am mad that I haven't been able to do some things," Lee says. "I haven't had much of a childhood. There was no such thing as a sweet 16. While people were getting punished and allowance, I was out here trying to pay bills. But I use my experience to my advantage to help other people." "We have kids that have a lot of baggage, but they are kids just like everyone else," Lake Clifton Assistant Principal Eugene Leak says." He notes that this year's valedictorian is going to Cornell University, and that "the number of students going to college is growing from previous years." Out of 251 graduates from the class of 2002, 38 went on to two-year colleges and 96 to four-year colleges; out of last year's class of 219 graduates, 19 went on to two-year colleges and 80 to four-year schools. Even in a school system with inherent handicaps to learning, the city's public schools do employ some dedicated professionals who prod and assist the students. "We had a business program that I was in," Lee says. "We had a law program. One of my English teachers had us read Charles Dickens, and we related it to poverty now. He was one of those teachers that opened up my level of thinking." While Lake Clifton does offer some good programs, "kids have to take charge" of their education, Lee says. "School is fine for me, because I try to stay focused--I have never been the type to hook class." In addition to being a good student taking a full course load, including pre-calculus and physics, Lee ran track; played softball, tennis, and volleyball; and co-founded and served as vice president of the school's Gay-Straight Alliance. She will attend Potomac State College in West Virginia in the fall. "I want to do physical therapy, so I was looking for colleges that offered physical therapy [majors]," she says. "I sent away for colleges in New York, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico. I wanted to get away."

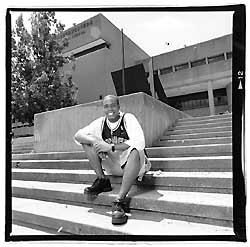

Kareem Everything is calm and quiet at Southwestern High School one humid day in June. The teachers are friendly and the staff professional. There are no loiterers in the halls. There is no evidence of the violence and turmoil that has plagued the school in recent years. Three years ago, for example, a student was shot just feet from the front doors, moments before school opened. "A lot of the students have problems at home and they bring it to school," says Southwestern student Iqbal Ali, who is graduating with an 80 average and will be attending Queens College in New York in the fall. "A lot of students that are intelligent, they don't do anything in school because they want to be cool. They have to realize the people they are trying to impress are not going to be around." "I don't find being ignorant cool in any way," says another graduating student, Kareem Branch, who sports an athletic outfit and a backward visor as he sits in the school's computer lab. "People respect you when you have knowledge." Branch, who won a full scholarship to the University of Maryland, remains fond of Southwestern despite its many problems. At one point he mentions that he has watched "three or four principals leave" in his four years at the school. But, he says, "people have to make the most out of their experiences," and he has certainly made the most of his own. Branch earned his street smarts growing up in the Freemount/Lafayette section of Southwest Baltimore. His father has been in jail since he was 2, and his mother struggled to raise him by herself, depending on welfare for a time. "It used to hurt me that there were things I couldn't afford to get him," says his mother, Sylvia Wands, who now works in marketing at Sam's Club. "There were times I had to take him to work with me so I could continue working." With his father and most of his older male cousins in and out of the correctional system, Branch says he has had few role models besides his mom. "Growing up with all this negativity--by the time I was 8 years old, I decided to succeed," Branch says. "I used to visit my father [in jail]. I don't have anything against him, [but] I didn't let his negativity influence me." "He didn't like to go there," Wands confirms. "He said that wasn't a place he ever wanted to be." Even now that he has had some success, Branch says that some members of his own family question what a college degree will really mean in a society they say will judge him by the color of his skin rather than his education and skills. On a sunny July 14, the University of Maryland campus is fairly empty. A throng of teenage girls cradling lacrosse sticks walks toward the lush green practice fields behind the sparkling new Comcast Center. Byron Mouton, the small forward from the Terrapins' national championship basketball team walks with a teammate near Cole Field House carrying a bag of snacks. This is the first day of orientation for winners of the Baltimore Incentive Award Program, a UM-sponsored scholarship that awards one exceptional student from each of Baltimore City's high schools with a full academic scholarship. Branch, who graduated with an 83 average, is the Incentive Award recipient from Southwestern. "People always ask me if I am getting an athletic scholarship," Branch says. "It is pretty insulting." Branch and his mother have made the trek with sheets, clothes, and the most essential item--a PlayStation II--in tow. Incentive Award students are getting the chance to meet other students from city public schools and form their own community before the fall semester starts. A range of counselors, psychologists, and professors are on hand to warn of the difficulties they'll face in college, from time management to avoiding financial pitfalls such as predatory credit-card companies. Branch already knows he wants to study hospitality. He was in the Academy of Travel, Tourism, and Hospitality at Southwestern and has worked downtown at the front desks of the Holiday Inn and the Clarion Hotel. "When I worked at the Clarion they wanted me to be a supervisor, but I was only 16 years old. I didn't want to work from 4 to midnight every day and go to school," Branch says. "Plus, I wouldn't have felt comfortable supervising adults." "He was working like an adult," Wands says. "He would work on the weekends [too]. The guy who did his taxes said he had never seen a teenager make this much money. He doesn't like to let people down, but I tell him he has to take a break too." Not only did Branch work a six-hour shift weeknights at the Holiday Inn during the school year while maintaining his grades, he also freelances as a Web-site designer for small businesses around the city. But hardly a square, Branch is outgoing and laid back. Teachers and counselors describe him as one of the best-liked students at Southwestern and someone who excels at "selling himself." He used his salesmanship and Holiday Inn connections to host a rooftop party after his prom. He DJ-ed the party himself with selections from his vast CD collection. By the middle of his first week in College Park, the summer session is in full swing and Branch has begun his journey into college life. Although he misses many of his friends at home, Branch says he has given little thought to the changes that are taking place at Southwestern. In the future he will be invited, along with other Baltimore Incentive Award recipients, to speak at his alma mater and tell of his experiences. By then, his school may exist in an entirely different form and students like Branch will simply be the expected outcome of the system rather than an anomaly. Branch says he isn't having trouble keeping up with college-level coursework and has already earned an A on his first English paper. He says that many of the professors are aware of the poor reputation of Baltimore public schools and have been somewhat surprised by the level of achievement the Baltimore Incentive students have maintained. "Coming from Baltimore schools makes it seem like I have a ton of stuff to prove," Branch says. "But it is also an honor to me because, anyone that has something bad to say about us, I want to prove them wrong."

|