|

Jazz Meets Hip-Hop |

|

|

|

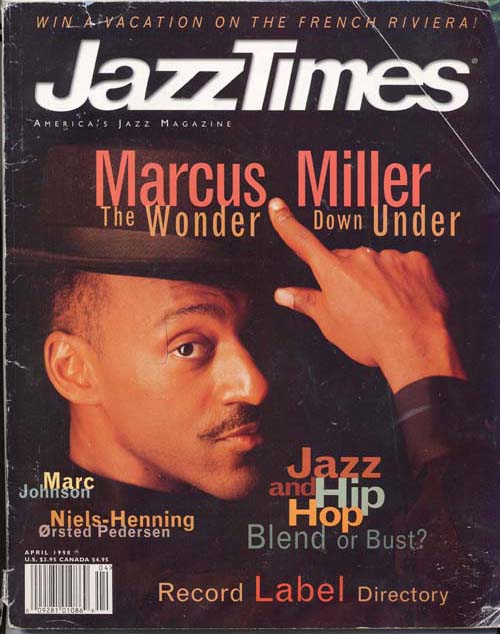

JazzTimes Magazine, 1998 |

|

“Hip hop is like one of the children of jazz music” -Nas “When I was coming up it was mandatory to know something about music and play an instrument. In order to do this it required hours of dedicated study and practice. Today if you can just rhyme and talk and have a talent for matching words and rhythms together you pretty much are on your way; it wasn’t quite that easy when I was coming along.” –Jackie McLean By Ericka Blount With the next millennium fast approaching, we are witnessing a musical and cultural phenomenon—a collage-producing jump-cutting, mix and match blending of American urban music—jazz and hip-hop. Not that this strikes a lot of folks as good news. Some see hip-hop and jazz as an unholy alliance, the trivialization— maybe even vulgarization of jazz, that great American art form. But musicians who share the same bloodlines often see the genre-melding as a positive development. More and more these days, in fact, the offspring of famous jazz musicians are experimenting with jazz and hip-hop hybrids—with their parents’ blessings. Quincy Jones’ son, QDIII, is a rap producer. The sons of Ornette Coleman and Roy Haynes are also involved with the music. Kenyatta Bell, the son of bassist Samuel Aaron Bell, produces rap records, as do the sons of saxophonist Marion Brown and Horace Silver— Djinji Brown and Greg Silver. Three generations down the line, rap producer Rene McLean is part of an emerging musical dynasty, being the son of saxophonist Rene McLean, Sr., and the grandson of sax legend Jackie McLean. Many of these artists were happy to discuss the trend toward blending the two musics—the problems, the promise and the controversies. In some ways the musical connection would seem inevitable. After all, early gospel, blues and jazz employed call- and-response cadences dealing with the same themes prevalent in hip-hop—— procreation, braggadocio, and overcoming overwhelming odds. One obvious difference is that the hip-hop artist today is dealing with far less subtlety in the language—where Bessie Smith called for “A little sugar in my howl, a hot dog in my roll,” rap artist Lil’ Kim is doing nothing to masquerade her desires. For some, though, the similarities end there. Straightahead jazz musicians who have had their music sampled appreciate their work being exposed to a new audience, but they often have a hard time actually understanding the music—or, for that matter, even calling it music. Just as the older jazz generation decried rock ‘n roll, convinced that good music ended with Nat King Cole, Sarah Vaughan and Ella Fitzgerald, the current generation of jazz fans have frequently objected to hip- hop. To them it’s just another symptom of urban and moral decay. By the same token, while hip-hop artists sample the work and listen to the music created by jazz musicians, most hip hop fans have shown little interest in hearing jazz musicians perform live. Further complicating the issue is the fact that early attempts to fuse jazz and hip-hop weren’t always successful. Rap artist Guru’s Jazzmatazz album which features Ramsey Lewis and Donald Byrd, is typical: the hip-hop rhythms and jazz elements never gel; they’re merely tacked together. Several other collaborations featuring hip-hop artists and jazz musicians have been unsuccessful, failing to do justice to either form of music. Not only does the jazz musician generally find his role limited, the hip-hop artist sometimes comes off sounding more conservative than he would when left to his own bass-driven devices. Seminal projects like Miles Davis’ Doo-Bop, produced by Easy Mo Bee and featuring jazz solos overlaid with rhyming, have proven to be disastrous when it came to enhancing both forms of music in an amalgamation. On the other hand, when A Tribe Called Quest used bassist Ron Carter on the track, “Verses from the Abstract,” or when trumpeter Olu Dara collaborated with rapper Nas, the results were far more impressive, primarily because both parties—the jazz and the hip-hop musicians—were allowed to express themselves freely while complementing each other. The notion that hip-hop will somehow taint jazz strikes Dara as ridiculous. “When bebop [arrived] the same type of controversy came, the first jazz bands in the early 1900’s had the same controversy,” he said, sitting in his living room with his son, triple platinum rap musician Nas. The veteran trumpeter and composer clearly views those who oppose blending the music as misguided. “Jazz people are in no position to put down hip-hop or any other black music, because all of the music comes from our hearts, our voices, our God-given instruments.” Aaron Bell agrees—to a point. The 74-year-old former bassist for Duke Ellington believes that hip-hop is being met with the same resistance that jazz was in his day, but he doesn’t believe that rap qualifies as music. “I think rap is a form of entertainment. I wouldn’t say it was music because it needs composition, melody, rhythm and harmony,” he said, while dining with his son in The Sharkbar, a Manhattan soul food restaurant. Bell, of course, is touching on one of the key differences between hip-hop and jazz: Hip-hop is about saying, not playing- —it’s the expression of a street culture, developed by kids with no other musical resources than their parent’s records and eight track cassettes. Bell’s son, Kenyatta, offered his own take on the cultural milieu that gave rise to both hip-hop and jazz, “Hip-hop started basically from the concept of rocking a show—an MC, a mike, and a crowd. And that is exactly what the conditions were for jazz—jazz was small, intimate jam sessions.” “I don’t make distinctions between jazz and hip-hop because one’s existence is dependent on the other,” insisted alto saxophonist Rene McLean, Sr., on the phone from South Africa, where he currently resides. “It is just another manifestation of creative expression as a link to the reality of black folks and black youth in particular. Jazz has always had to deal with where a people are in that time and place in their history and how they view their world and the communities they came out of . . .whether or not they have had access to cultural programs, whether or not they have been exposed to music or art in their communities and the schools they go to have an impact on how they express themselves.” Many forms of African American culture have been born out of a lack of resources, including go-go music in DC. But hip-hop has proven to be the most expressive, both verbally and musically. Go – Go compensated for the lack of musical instruments in the classroom by substituting items such as trashcans and sticks for instruments. Hip-hop went as far as to create sounds and beats with vocal expressions. The human beatbox filled the void of musical instruments, until advanced computer technology led to other creative ventures. Both the human beatbox and sampling made a radical break from what some have previously considered music. As a result, rap’s in-your-face brand of music hasn’t appealed to the more conservative jazz listening audience. Hip- hop lyrics are being met with the same resistance encountered by bebop musicians (and even R&B musicians like Marvin Gaye and James Brown) when they developed new forms of expression or addressed topical issues. What’s more, some older listeners feel that the hip-hop rebellion has gone over the top. With violent deaths of rap musicians like Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur, many have even become fearful of rap artists and turned off by the music. Looking for easy answers, many people are looking to blame the artists rather than the times. “I like some of the music, even though the negative aspects lie around what is the message that the rappers are talking about,” said Jackie McLean, referring to the controversy’ surrounding the lyrics of some rap songs. “All of that ‘boyz in the hood’ stuff got boring to me after awhile because it is just more and more of the same—guys with hoods on and standing in front of big garbage cans on fire, loaded down with guns and stuff. Even though it is a message about life in America today-, I would much rather find out how we can remedy some of this stuff rather than perpetuate it.” The process in hip-hop of sampling— borrowing loops, the tracks, or the lyrics from songs of the past—has also been criticized by many for not being creative. Djinji Brown, who went from being a rock singer in a band, to break-dancing, to eventually diving completely into hip- hop, believes that while many hip-hop artists are not able to play instruments, sampling is nonetheless a creative process. Hip-hop artists, after all, can create an original piece of music by sampling snippets from several tunes. At the heart of both types of music is improvisation the ability to be quick and creative on your feet. “Hip-hop culture from the art, the murals, graffiti and especially the music is so non-academic, you know what I’m saying, there is no classroom training for doing it,” said Brown from his Brooklyn based studio, “I think that frightens a lot of people because it goes against the grain of what we’ve all been taught you gotta do to master something.” His father, Marion Brown, couldn’t agree more. “He is the young man that I wanted to be,” Brown said of his son, who’s the inspiration for his tune, “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun.” “I think he is fantastic. The thing that gets me is that he can do as much as he can because I know that he doesn’t know a whole note from a half note,” he added, laughing. Nas, who’s already sold more records than most jazz musicians will in their lifetime, sees hip-hop as a natural extension for jazz expression. “My father’s style is laid back, old school jazz player type—intellectual shit going on. My shit is the same way, but from a young perspective, living right now in the New World Order.” Rene McLean, Jr., national director of rap promotions at Elektra Records concurred. “It is similar in the way that the artists feel about their music, a whole mindset. I think a lot of jazz artists are concerned with selling out to a certain degree, playing the softer sort of jazz, CD 101 type sounds, and you have the rap artists who are just as concerned about that whole crossing over.” QDIII who has produced artists like Tupac, and scored movies and television programs, agrees with Rene about the way the artists feel about their music, but notes that one of the differences between jazz musicians and rap artists is in the control of their music.” I think one thing hip-hop has managed to do, I don’t know if that is because we have seen what happened to jazz, but it seems like we took a lot more control—brothers own a lot of the companies—and to some extent brothers are the only ones who can promote hip-hop.” Quincy Jones—the man who needs no introduction—is one of few jazz musicians who has worked in many fields—as a pop, jazz and rap producer and as a jazz musician. “When my son was little, we went to New York for his birthday, he wanted to meet all the rappers because he was a professional break dancer. So we went to a party with Russell Simmons—I mean every rapper on the planet was there,” said Jones on the phone from California. “My son reminded me of how excited I was when I first came to New York seeing Miles, Dizzy, Bud Powell, and Fats, and all those people. Rap is the newest member of the family of black music—rappers go way back to the griot in Africa—it is not like it started out of the blue.” Most likely the

children of the rap generation will disagree with their parents’ view

of music, while hip- hoppers will insist that great music ended with

Tupac, Biggie and A Tribe Called Quest. But as Duke Ellington said there

are only two types of music—good and bad. Clearly, jazz musicians and

their hip hop children are travelers on the same train, but on different

cars. It will be interesting to see what the future holds, as hip-hop

musicians closely watch their children to see what comes next.

|