|

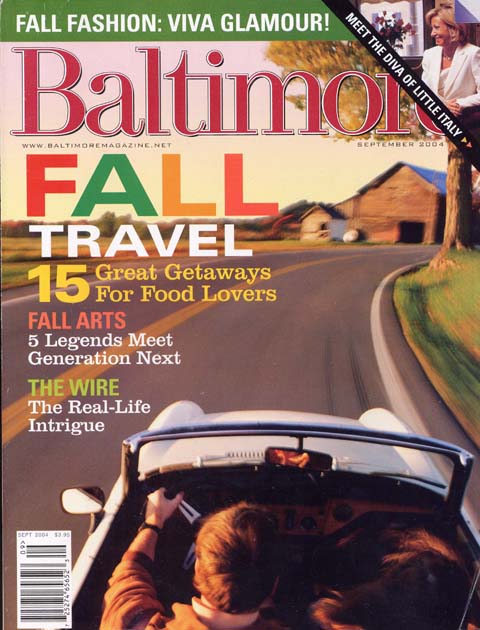

Little Melvin on HBO's "The Wire" |

|

|

|

Baltimore Magazine, 2004 |

|

Respect Twenty

years ago, detective Ed Burns helped put the notorious "Little

Melvin" Williams in prison. So why would he hire him for

The Wire? By Ericka

Blount Danois Melvin

Douglas Williams waits in a small room off of the main entrance to the

Bethel AME church on Druid Hill Avenue, wearing his signature all-black

clothing. A black towel draped over his shoulder,

yellow tinted sunglasses by his side. A picture

of a crucified, brown skinned Jesus hangs on the wall to his left.

In front of him are lockers tacked with BELIEVE stickers. As camera crews, extras and

cast from the third season of the HBO series The Wire mill

around him, Williams sits in a red leather chair, self-possessed and

indifferent to the confusion around him. Bethel AME is his

church, but today, it's where he will work on his acting chops. Moments later, Williams is

sitting in a pew, facing stained glass windows, filming a scene in which

he counsels a young man trying to get his life in order after being

released from prison. Williams plays a deacon at this church, a man

whose job it is to tend to wayward souls like the one now before him. "You want a job, you've

gotta work to get it," he says to the youngster, his voice musical,

soft, connected. "We'll help you, but it will be your sweat." Bibles rest in the shelving

of the pews. The camera focuses on their covers, and the scene ends.

People begin moving around and talking. In a few more minutes,

they'll shoot the entire scene again. In one small corner of the room

sits Ed Bums, a former Baltimore City homicide detective and now a

producer on The Wire.

Twenty years ago, Burns participated in the investigation

and raid on "Little Melvin" Williams's property that

confiscated $100,000

worth of furs, more than $27,000 in cash, and Williams’s

prized $52,000 black

Maserati Quattroporte. A year later, in March 1985, The

Sun's headline read "Little Melvin Sentenced." A federal

judge had sent Williams to prison for 24 years on drug-related charges.

The article was written by then-Sun

reporter David Simon, who

co-wrote The Corner with Burns, and is the creator and executive

producer for The

Wire. (Next to that article was one written by Rafael Alvarez,

also a co-writer on the show.) Two decades

after Burns helped send Williams to jail, he's ended up giving the

former drug kingpin his first acting job. It's only fair, considering

that many of Williams' exploits have served as

inspiration for Burns, Simon, and the other writers.

They've even placed the 62-year-old "Little Melvin"-who is an

avowed born again Christian-in the role of a deacon for the macabre,

tough police drama. Burns says that Williams is

a great actor with a photographic memory. "We get a lot of guys

off the street try to do this and they choke," Burns explains.

"He has a calmness about him that allows him to be this

character." "LITTLE

MELVIN" WILLIAMS'S REIGN OVER the city's heroin trade in the 1980s

provided fertile ground for the show's writers: Stringer Bell-one of the

top lieutenants to The Wire's ruthless criminal mastermind Avon Barksdale-operates a

photocopying business as a front company for drug sales; one of

Williams's top lieutenants, Lamont "Chin" Farmer, owned

Progressive World Press on North Avenue, which was a front for the drug

business. On the show, Barksdale owns a strip joint named Orlando's,

which is similar to Williams's old Underground Club on Edmondson Avenue.

And like Barksdale, Williams operated a very sophisticated drug ring,

creating codes for pagers that seemed impossible to unravel. Because of the ingenuity of

Williams, Baltimore City detectives sought and obtained the first

wiretap warrant in the country for information coming off of a pager.

Burns remembers that even with the wiretap,

it was hard to

nail down a gang as sophisticated as Williams's. "Chin [Farmerl

would get a page and he'd walk a couple of blocks to the pay

phone," Burns explains. "Then Melvin would get a page and walk

to a phone booth. These phones would be wired up [tapped]. We'd have two

machines recording it. "So Melvin says to Chin, 'How's your bank!'

and Chin is saying, 'I am one mark shy of the mark,' and Melvin says,

'Meet me'--which we couldn't make heads or tails of. And then they met

in Melvin's Maserati and whatever conversation they had, they had.

That's how cautious they were." A hustler at heart,

Williams's initial mainstay was gambling, and his prowess earned the

attention of Julius “The Lord" Salsbury, a top associate of

Jewish gangster Meyer Lansky--a rarity, as strained race relations were

the norm even in crime. He eventually became a godson to Salsbury, and

later gained entry into the inner circles of the infamous New York based

Gambino crime family. In 1975, Williams was

sentenced to 15 years in federal prison for narcotics distribution-on

the word of what he and Burns both agree was a corrupt informant. "His first conviction

was a setup by the government." says Burns. "It was a sham;

they planted drugs on him." "But that didn't matter

until I had gone to the penitentiary." says Williams about the

arrest. "So I decided that since you have made me a drug dealer, I

will give you a drug dealer you will never forget." Williams was paroled in 1979,

and Baltimore would never be the same. He became

Baltimore's main supplier of heroin, a substance that plagues the city

in epidemic proportions to this day. At its peak, Williams's operation

employed some 200 dealers and made millions of dollars a year; he owned

dozens of properties and vehicles, and his gang waged a campaign of

violence and intimidation throughout the city. Federal, state, and local

authorities finally arrested Williams in 1984. He would spend the next

13 years in federal penitentiaries across America. Williams--who says he has

dedicated his life to Jesus

Christ, and serving God--was paroled in 1997. He was arrested in 1999

and charged with using a handgun to beat a man on a West Baltimore

street (a parole violation). Facing another 22-year sentence for this

violation-which would have kept him in prison well into his 80s-he was

released by a judge in January 2003. Within 24 hours of his

release, he was re-arrested for the 1999 parole violation by federal

authorities, who felt he had been unlawfully released.

Eventually, things were

settled, and Williams was set free in September 2003. Soon after that,

he got a phone call from David Simon and Ed Burns. They wanted to take

him to lunch at Mo’s Pasta and Seafood Factory in Little Italy and

talk to him about The Wire. "They

were joking with me about my photographic memory," says Melvin.

"and the suggestion was that my memory would he good for

remembering scripts." So they hired him. WILLIAMS SITS

AT A SMALL WOODEN table at a warehouse in a Baltimore city

neighborhood. Outside there are several young men busily working at a

flea market, selling an assortment of goods including flavored ice and

radial tires. "I respect him, unlike

many police officers I've met," Williams says of Burns, speaking

slowly and deliberately, never cracking a smile. "He never

straddled the line. Didn't fabricate evidence.

He had one agenda--to put Melvin in the penitentiary. He was as

honorable and as sincere at being a cop as I was at being a criminal."

Many believe that Williams's sins are unforgivable. One judge told him

that no matter how many times his hand has been touched by God, he will

never be anything more than a criminal. Ed Bums doesn't agree.

"In my book, if you do your time, that's it." he says about

any criticism for hiring Williams. But right now, Burns can't

worry about things like that. He has more immediate issues like making

sure the storyline has suspense and that the dialogue sounds right,

making sure it will grab the audience. It doesn't hurt that now he has a

little more help to make sure things are authentic. "Melvin is very

disciplined, so it was no surprise he was a good actor," says

Burns. "Hopefully." he

adds, "he's staying straight." The crew is preparing to resume

filming. Williams waits patiently for his cue. He's asked about how

surviving his past informs what he tells to the at-risk youth he

lectures regularly. "I spent 26 I/2 years in all of [America's]

worst penitentiaries-to say I survived is misleading," says

Williams. "I tell young people who think they have the opportunity

to live my life over that the probability of success at being a criminal

is almost nonexistent, and that doom is ultimately part of the

process." There is a rush of activity

as everyone takes their places. One of the directors calls out,

"Set, rehearsal, eight seconds, seven, six, five, four . . . Ready

everybody? And . . . action!” And Williams begins to act.

|