|

The Family That Plays Together . . . |

|

|

|

City Paper Online, 2003 |

|

Meet the Featherstones--Two Generations of

Professional Musicians, Educators, and Now Hitmakers

RaRah

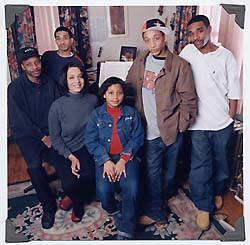

Family Portrait: (from left) Lurenda, Justin, Tegra, Chard',

Christopher, and Matthew Featherstone in their living

room/music-school dance studio.

Keeping the Beat: When not playing drums, teaching lessons,

shopping demos, working, or helping raise his family,

Lurenda Featherstone gets some sleep: "At work we get

two 15-minute breaks."

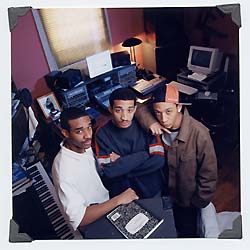

Teen Beat: (from left) Matthew, Justin, and Christopher

Featherstone cook up tracks in Roundtable Productions'

studio, aka the family den.

Some might say it all began at Security Square Mall in the summer of 2001, when The Baltimore Times hosted its annual Uplifting Minds talent show. Sisqó, the flamboyant, red-haired member of the Baltimore-bred R&B group Dru Hill, was in attendance and heard the Featherstone boys sing one of their own songs. They didn't win first prize, but Sisqó was impressed with their sound and gave them his phone number. When he was slow in getting back to them, tenacious father Lurenda Featherstone took matters in hand. He placed a quick call, leaving a message on the singer's answering machine: "I heard your last album wasn't so good--you better call me back if you want a hit." Maybe it was Dad's boldness or his sons' arresting sound, but Sisqó called right back. "After my husband called him, Sisqó came over to our little house," says Mom Tegra Featherstone. "I was in the kitchen cooking--my daughter was scared of him and she was hiding under the table. He told us he really liked the song and wanted to record it for his album." Cut to late 2002: Dru Hill is once again blazing the commercial-radio and music-television stations with its latest hit, "I Should Be." The single, written and produced by 21-year-old Justin Featherstone, 19-year-old Matthew Featherstone, 16-year-old Chris Featherstone, and their production team, Roundtable Productions, has pushed its way into the top 10 on the R&B charts and energized Dru Hill's triumphant re-emergence onto the music scene. But the Featherstone story really begins 25 years ago. In 1977, at the tender age of 19, Tegra Johnson was playing keyboards for a Baltimore funk band named Manna. Lurenda Featherstone, also 19, was playing drums in a local band called Moon August when not touring with jazz legends like Kenny Kirkland, Doc Powell, Marcus Miller, and Horace Silver. Lurenda needed to return an acoustic bass a friend had borrowed from a member of Manna, and it turned out Manna was looking for a drummer to fill in from time to time. Lurenda accepted the offer. Tegra and Lurenda became fast friends and within a year they eloped. "My mother asked me, 'Where are you going?'" Lurenda remembers. "I told her, 'I am going to get married.' She didn't even look up--she just laughed and said, 'You crazy!' "We eloped with $50 and a used Pinto," Lurenda laughs. "It was such a beat-up car, the car doors wouldn't open. After we got married we went to a nice restaurant, looked around, and crawled out the windows." Despite the fact that they were both musicians living in Baltimore, the two had no reason to think they would ever cross paths, much less collaborate in music and in life to the extent that they have. Tegra grew up on North Avenue and Bentalou Street near Mondawmin Mall and began her musical education when she was 5 years old, taking free lessons from Peabody Conservatory faculty member Helen Doyle, a friend of her mother's. By the time she was studying in the music program at Douglass High School, Tegra was already playing clubs with Manna. Lurenda went to City College High School and grew up in the Mount Washington neighborhood where the couple lives now. When he was 7 years old, he wanted to take drum lessons, lessons his mother couldn't afford. When he learned that a neighbor, Nat Conway, taught drum lessons, the outgoing and resourceful Lurenda went to Conway's house and asked if he could take lessons from him. From there he started playing in the church where his father was a minister. "I was one of the first drummers that played in churches--back then they didn't want you to play drums in the church," he says. "I started with snare drum and gradually eased the whole set in. "Our group was called Little Willie and the Whispering Spirits, and we had a three-foot-tall midget playing the guitar--I was just a little bit taller than him," he laughs. "We were a quartet and we would play for churches and we released records." "He was so small we would have to take a stool to church and set him up on the stool," his mother, Elizabeth Featherstone, recalls of her son. "But he had to play." By age 8, Lurenda had moved on to play with a girl group called the Five Stars that recorded for Savoy Records. The group performed as far away as Spain, though it toured only on weekends so Lurenda could go to school and other band members could go to work during the week. But even while launching a professional musical career, Lurenda stayed on the honor roll at school. His mother, who now lives next door to her son and his family, says she still keeps all of his "good papers." The devotion is mutual. "My son still comes over and cuts the grass for us--he does things for me and my husband because we done got up in age and we can't do like we used to," Elizabeth Featherstone says. Lurenda's fierce dedication to family is evident. In the middle of a phone interview, a voice in the background asks him how much longer he is going to be. He apologetically admits he has to go because his mom needs him to move some furniture. Lurenda's dedication kept his own fledgling family together in its early years. By the time Tegra and Lurenda had their first son, Justin, in 1981, they were renting an apartment for $150 a month in a house full of musicians on Woodbourne Avenue. They were struggling to make ends meet on Lurenda's part-time salary as a United Parcel Service truck loader and the money coming in from his work as a freelance drummer while Tegra studied music through the prestigious Trinity College of London music program at Towson University. Though Tegra says Lurenda was a hands-on father, getting up in the middle of the night when the children were babies, she recalls "it seemed like I was always nursing. Lurenda would go out and come back, and I would still be sitting in the chair, nursing." But, being young, she adds, "It seemed like I always had a lot of energy." Her mother, Gloria Johnson, says she never minded Tegra getting married so young because she and Lurenda were such a "good pair. She came from a family that loved music and she was fortunate to meet a man that loved music. Now they have this whole family of musicians."

Though it took some effort and compromise to blend Tegra's classical training and Lurenda's jazz background, the Featherstones formed a duo known as the Featherstone Band. For years, they played local gigs and used the money to augment Lurenda's UPS wages. But the Featherstones had bigger dreams. In 1991, Lurenda delivered packages every day to a airplane-part manufacturer called A&M Machines. Every day he would shoot the breeze with an old man who would sit out in front of the building. "I used to tell him everything I wanted to do with the music--I had no idea he was the owner of the company," Lurenda says. "When one day he told me, 'I want to help you out,' I thought he was joking. He asked me how much it would cost to start up a label. I said probably about 10 grand. He wrote me a check on the spot for 20 grand." The man, Andrew McNeil, became the Featherstones' financial backer and close friend. "If he believed in somebody he would help them," Lurenda says. The Featherstones' Clean Music Records went on to release four jazz albums, including a well-received session from local drummer Larry Bright. But just as things started to take off for the company, McNeil died in 1997. When he died, Clean Music died with him. "I got left with all the bills," Lurenda says, recalling bill collectors calling the house constantly. "We are just coming out of that." But even though the company folded, the Featherstones had already made the connections in the music industry that would lead to their next business venture: a music school. Just a few decades ago, most public schools offered some kind of instrumental music program to their students. "When I first came in 1954, the music program in Baltimore City schools was tenfold to what it is now," says Thomas "Whit" Williams, a saxophonist, bandleader, and educator who has taught music in Anne Arundel County public schools for more than 30 years. "In the 1960s there were bands in almost every high school in the city. There were students at Douglass High School who already had the level of theory that was taught in college classes. Douglass had a fabulous reputation for turning out fabulous musicians." In 1998 only 16 out of the city's 123 elementary schools had instructional music programs. A Sept. 23 Sun article pointed out that city schools haven't purchased a musical instrument since 1982. Williams says the level of instruction in public schools has suffered as well. "A lot of the teachers in the programs now have [music] degrees, but they have never played [professionally] before," says the veteran musician, who has played with Nancy Wilson, Michael Jackson, Jimmy Heath, and Liberace, to name a few. Williams laments the loss not only to the musical education of Baltimore's school children, but to their general education as well. "They have done all types of studies that say kids who study music do better in all other subjects, and through my personal observations I agree with that," he says. Of course, when music programs started leaving the school systems because of a shortage of resources, kids started getting resourceful themselves. From go-go music's use of trash cans and sticks for instruments, to hip-hop's human beat-boxing, to recordings built entirely from samples of other recordings, creative musicians have found ways around a lack of proper training and access to instruments. But with the advent of sampling came criticisms from instrumental musicians who had taken years to perfect their craft that this was the end for black music. As artists started sampling relentlessly, it seemed the need for instrumental music would soon diminish. But the Featherstones are on a personal mission to share their love and appreciation for conceiving and producing good music, founding Featherstone Music Instructional Inc. in the family home in 1987. The homegrown school has turned out exceptional musicians such as Maimouna Youseff (Arts and Entertainment, Dec. 18, www.citypaper. com/2002-12-18/music.html), Larry Crockett, and Richard Burton in the process. All members of the Featherstone family, including their youngest child, 9-year-old daughter Chardae, have taught at the school, which offers lessons and classes seven days a week. Despite the number of years the Featherstones' school has been around, it is still a humble arrangement. The family dining room acts as a classroom for music theory. The living room doubles as a dance studio and houses two pianos buried under music programs and books. A small den off of the dining room serves as a professional production studio. The basement contains a full drum set for lessons. On the kitchen floor sits a large stereo system with various CDs and open CD covers scattered about. Pictures of instruments adorn the walls, and family photographs are present everywhere. It may look humble, but the week after Christmas the Featherstones installed a new telephone line to take in business calls. When they appeared on the Mark Clark show on WERQ (92.3 FM) on Dec. 13 and gave out their home number for people interested in the school, the flood of calls forced them to install a business line. There is so much demand that there is a waiting list. The school draws its clientele from a diverse group spanning senior citizens from the nearby senior-citizen home who are interested in music lessons to precocious toddlers. "We have 4-year-old kids that walk through the door and will slide on their stomachs all the way over to the piano--then we say you can do the dining-room floor next," Tegra says with a laugh. "They are very easygoing," says Joan Turner, whose grandson has taken lessons with the Featherstones. "They don't seem frustrated. After teaching for awhile, you get tired and burned out. But theirs is a house you go into and you feel absolutely comfortable." Fees range from $30 to $75 a month for piano and drum lessons as well as music theory, vocal instruction, and music composition and production classes. Students can also take part in the "Bach to Blues" program, which combines classical with jazz. And the Featherstones offer lessons on the music business, from publishing and copywriting to what lawyers to look for and what kinds of contracts potential superstars should and should not sign. Such business savvy comes in handy. It's a hustle to keep the music school going. In addition to caring for a large family and running a business, Lurenda still works nights at UPS while Tegra works part-time as a customer-service agent at United Airlines. In addition to work and running the school, Fridays often find Lurenda on his way to New York to tout songs written and produced by Roundtable Productions to major-label A&R people. Lurenda has been working the night shift at UPS for five years now; he says he averages five hours of sleep out of every 24: "At work we get two 15-minute breaks. I go to sleep, and when I wake up I feel like I have slept for a long time." Yet somehow the Featherstones are still able to put family first. Tuesday nights were always family nights. When the kids were younger, they made fun activities out of Bible lessons, put on plays with Bible characters, and played music in the background. "And some Tuesday nights we would just talk--especially when they were teenagers," Tegra says, adding that they still continue this tradition. The next generation of Featherstones have obviously benefited from the tight family bonds, and from growing up in a music school--especially Justin, Matthew, and Chris. It is a dream come true for Lurenda to see his sons become as successful in music as they have been so far, especially since he gave up some dreams of his own. When he was their age, he won an audition with the world-famous jazz-fusion group Weather Report. "I was going to go [out] with Weather Report--they wanted me to do a six-month tour in the Orient. But we had just had a son, and I didn't want to leave my family," Lurenda says. He recalls a conversation he had with jazz/R&B singer/guitarist George Benson, "who told me he regretted touring because he wasn't close with any of his sons. That really affected me. I know the impression a man can have on a [young] male." "He was featured in Modern Drummer magazine," Tegra says. "He was one of the best drummers in the U.S., and I am not just saying that because I am his wife. He sacrificed a lot, so it is really great for him to see the success the boys have had." "[Lurenda] is a fabulous drummer, a supertalent in percussion," echoes Whit Williams. "He could have done anything he wanted to do." "I did go through a depression for a time," says Lurenda, who still gigs now and then. "But I realize it was worth it. All of them are growing up to be stable young men. Me being there helped keep them out of trouble." "Lurenda could have been on the road making tons of money," Tegra says finally. "But where would our family be?"

At midday on Dec. 27, the cold and blustery streets are crowded on the strip of stores along Howard Street. Amid the shoppers, B-boys, and vendors, Christopher and Justin Featherstone are handing out copies of Watchtower magazine. As Jehovah Witnesses, each member of the Featherstone family dutifully fulfills his or her responsibility to spread the word. Of course, there's another kind of word the three Featherstone boys are hoping to get out in their free time. With the help of their father, they started Roundtable Productions about six years ago; in addition to Justin, Matthew, and Chris Featherstone, the team includes Alonzo Joyner, Jeriel Askew, and Donte Speaks. The Roundtable crew is currently shopping its new group, Mystory, to labels, putting its own group, Everidae (consisting of the Featherstones and Joyner), on the back burner. When Sisqó first heard the the quartet sing at Security Square, he talked of signing Everidae to his label. The first single they planned to drop was a song they had written and produced, "I Should Be." The quartet illustrated their vocal dexterity by singing the song a cappella when they appeared on the Mark Clark show on 92 Q.

'cause when there all I see is crying, I should be your boyfriend because you know he's lying, it might seem like I'm hating, but I'm just relating. Their rhythmic cadences swirled in unison and created a lilting sound equal to Dru Hill's trademark amalgamation of smooth melodies and rough, hip-hop-style vocals. But the song was bound for another fate and another set of voices. "'I Should Be' was what made Def Jam look at Dru Hill again, made them get behind them and put them back together," says Lurenda, who contends that the single sold the label on the platinum-selling group again after a long break between albums. As of press time, the song is at No. 7 on the Radio and Records R&B chart and No. 8 on the Billboard R&B chart. "It took us one night to write that song," boasts Justin Featherstone, who says the group averages writing and recording four or five songs a week. "We started writing at 1 in the morning and we started recording it by 2 a.m. For some reason, the faster we write a song, the hotter it is going to be, because we are just feeling it." While Everidae still lacks a record contract and a video in heavy rotation on BET, the Featherstones and the rest of Roundtable are biding their time, thanks in part to good career advice from a source close to home. "In the music industry the real money comes from writing the songs," Lurenda says, echoing the music-business lessons he teaches at the school. "A lot of these kids jump and sign these contracts and they get ripped off. People come down from New York to these talent shows, and they think people in Baltimore are country and ignorant and they rob them. A lot of these groups in Baltimore are getting robbed." The day before Everidae's appearance on 92 Q, the curtain hanging in a front window at the Featherstones' modest house on Levindale Avenue bears a silhouette of a young lady. She is nodding rhythmically and shaking her head from side to side to faintly heard music. Inside, one of the four members of the group Mystory, Lakeesha, is working with her vocal coach, Christopher Featherstone. He is taking the group--Lakeesha, Kyvonna, Nasya, and Chira, all still in their teens--through scales and breathing exercises before they launch into songs of love, friendship, and just wanting to hear someone talk on the phone. Lakeesha's voice is strong, but at the same time, it floats. Christopher sings along with a voice that belies his years; his sound is reminiscent of David Ruffin. The group rehearses on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays at the Featherstone house. "We train people hard if this is going to be their career," says Tegra. "If they are just here for cultural things, then we can have fun. But if this going to be their career, then we try to get as close to perfection as we can get." A few days after the rehearsal, the Featherstone family takes Mystory to be heard by a big-name music executive in New York. While singing scales with Christopher, the girls didn't yet know who it was going to be, but they were excitedly guessing Sean Combs and Clive Davis. Although neither guess was correct, their trip went well. "The senior vice president of Columbia was very impressed with them," Lurenda says. "People were running out of their offices to hear them." The Featherstone boys and their Roundtable imprint produce all of the group's music. It's a service they're performing for a growing number of artists. "For [the Featherstones] to be so young, they are very professional," says Richard Burton, a Featherstone student who has a day job as assistant to Mayor Martin O'Malley and who signed to MCA Records two years ago. Roundtable Productions has done a few tracks for his forthcoming debut album. Burton is impressed by the Featherstone boys' personalities as much as their skills: "They have a spiritual vibe--no drinking, no cursin'," though he cautions, "it's a good and a bad thing in the industry, because sometimes the good guys finish last." Christopher is a vocal major at the Baltimore School for the Arts and has been teaching vocal lessons for the jazz class this year; Matthew studies computer engineering at Morgan State University and has taught at the school for a year, taking on 20 piano students; and Justin, who doesn't teach at the school and mainly works producing in the studio, has taken a year off from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. But they are clearly hoping that their Roundtable careers take off even more than they have already. Their father likes their chances. "Big producers in New York can't believe these young guys are doing this," Lurenda says. Lurenda and Tegra have their own hopes for Featherstone Music Instructional. When the school holds a recital, the Featherstones must rent a space at the Eubie Blake National Jazz Institute, the Gilman School, or the Walters Art Museum. For the past 16 years, they have been holding annual fund raisers to keep the school afloat, to offer scholarships to students, and, most recently, to raise $2 million to renovate a building they are hoping the city will award to them. "We have been trying to get this space for two years," Lurenda says of the Stone Mansion, a building that used to house the old Waldorf School on Springarden Drive, just a few blocks from the Featherstones' home. "The city had awarded it to a Jewish organization that decided not to use it. It's just an empty building now." (Just a few days before this story went to press, the Featherstones say that city housing and community development officer Ed Anthony told them that no other organizations were interested in the building and that they should complete the paperwork necessary to qualify to take it over.) Their dream, if they are able to obtain the space, is to use the first floor as a coffeehouse/performance space. Some nights the space could be used to have jazz musicians come in and play; other nights it could be rented out to the community for receptions and weddings. The second floor would feature practice, dance, and drum rooms. The third floor would have two recording studios and a space for video equipment. A lot of people are hoping they pull it off. The Featherstones have given many low-income kids access to music, production, and writing lessons. And many single parents, who don't have the financial resources to afford instruction at other institutions, are enrolled in their classes. In addition to the Featherstones' lessons, there is the impressive example of a couple who have continued to follow their passions and pass on their creative talents to not only their children but anyone with an interest in learning. It's the day after Christmas, and the side streets in Catonsville are still filled with snow from the first Baltimore white Christmas in years. Michelle Buchanan sits in her music room filled with plants, books, bright flower-print chairs, a grand piano, and pictures of her five children: 17-year-old Kristopher, 14-year-old Pepper Michelle, 12-year-old Buffy, 11-year-old Keyonna, and 9-year-old Cubby. All five of her children studied music at the Featherstone School, but Buffy and Kristopher are the only two that have stuck with it. Seventeen-year-old Kristopher Buchanan, who is conservatively dressed, confident, and handsome in a traditional way--tall and dark with a bit of peach fuzz around his jaw--sits at the piano and practices scales before launching into a rendition of Stevie Wonder's "Ribbon in the Sky" in a deep, soulful voice. "Sometimes we just sit up at night and listen to him play," says his mom. "I would play guitar and I would sing to him when he was little. He paid attention and he would mimic the sounds. He was gifted." Kristopher was gifted in music, although his schoolteachers labeled him learning disabled. They told his parents he didn't have good hand-eye coordination and had trouble with math. Michelle Buchanan and her husband, Leslie, wanted to find someone who would be able to work with her son to hone his musical talents. "Tegra was so gentle," Michelle says. "By the time he was 5 he was playing with both hands. He also had a problem with memory, [so] they taught him using the Suzuki method. It is ear training--they are able to pick up anything they hear." She says Kristopher's music lessons have improved his concentration skills in school and that he just recently brought home his first set of As and Bs. Not to mention the fact that he can play Thelonious Monk's jazz compositions and tunes like Wonder's "Sir Duke." Feisty and slim, Buffy joins her brother at the piano and starts playing India.Arie's latest single, "Little Things." She has been playing with the Featherstones since she was 6 years old. "When Buffy was almost 4, she contracted a virus that attacked her brain. It left her completely paralyzed for months," Michelle says. "It was called acute cerebella ataxia--it was a case of chicken pox that went to her brain. The only thing she could do was blink. They said it happens to one in 5 million. "Every day we did physical therapy--it took her months to get back up. At first she had a walker. It was one of those diseases that takes hold of you and lets go when it wants to. "She started playing piano when she was about 6, and when she plays piano and sings, it is something else," Michelle says. "My girl can sing." Sitting beside her brother on the piano bench, she does.

Pure as a kiss on a cheek and a word that everything will be OK Call in the morning from my little sister singing to me happy birthday All of the Buchanan siblings sing along a cappella while executing an original dance routine reminiscent of the Temptations to go with the India.Arie tune. Their parents say they wake up to the sound of them playing music and credit the Featherstones for the "little things" they have done to hone their children's musical skills.

Got everything that I prayed for even a little more. . . .

|