|

Primm Family |

|

|

|

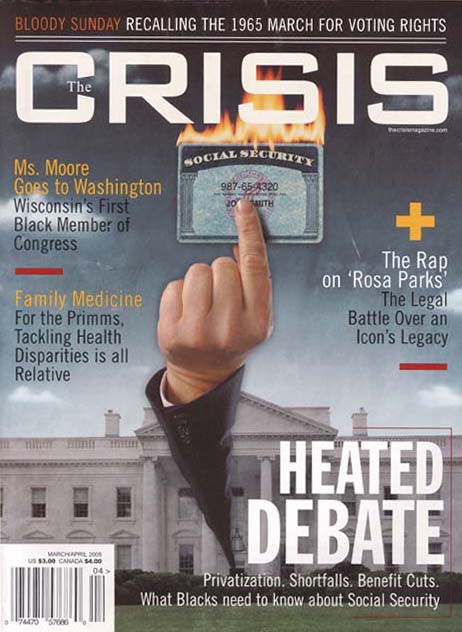

Crisis Magazine, 2005 |

|

THE PRIMM FAMILY MAKES BATTLING HEALTH DISPARITIES IN THE BLACK COMMUNITY A FAMILY AFFAIR BY ERICKA BLOUNT DANOIS On a cold Saturday in December, Annelle Primm sits at the kitchen table of Angela Jackson’s West Baltimore home listening to her recount her life as calmly as if she were reading a grocery list. Jackson, 40, talks about her mother who was never properly treated for manic depression and schizophrenia; about a rape in high school that resulted in pregnancy: a drug addiction that left her scaling drain pipes and sleeping on roofs; and the one person she trusted, a male best friend since middle school, who infected her with HIV. The story is all too familiar for Primm, who, as a psychiatrist, treats depression among minorities, particularly African American women. Many of her patients have dealt with issues of rape, drug addiction and diseases such as HIV/AIDS. She knows that African Americans lead the nation in heart disease, obesity, cancers, stroke, diabetes and kidney disease. But Primm also knows that many health disparities can be traced to a health care system that doesn’t treat Blacks the same as Whites. According to an analysis in the December 2004 issue of the American Journal of Public Health, “more than 886,000 deaths could have been prevented from 1991 to 2000) if African Americans had received the same care as whites.” Primm belongs to a family of health care professionals committed to addressing the racial disparities in the health care system. Their Baltimore-based company, Health Disparities Solutions (HDS) LLC, was established in 2003 to educate health professionals on the multiple ways health disparities impact not just minorities, but the well-being of the entire nation. HDS consists of Annelle’s father, Beny Primm. an anesthesiologist who has served as an adviser to three U.S. presidents: her sister Jeanine Primm, who has developed culturally relevant public health programs: and Annelle’s husband, Herbert Spencer, a compliance officer who makes sure physicians are providing quality care to their patients. HDS combines each family member’s individual specialty into a unique, comprehensive approach to health care. Former Surgeon General David Satcher, now director of the National Center for Primary Care at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta, is familiar with the Primm family’s work in the health care field. “They have been an outstanding family in dealing with some of the major health issues of our time and major issues dealing with the Black community— HIV/AIDS mental illness and substance abuse,” says Satcher. Head of the Family Seventy-six-year-old Beny Primm remembers from an early age wanting to be a doctor. He went to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, then an all-male institution, on a basketball scholar ship at age 10. But having attended all-male schools for most of his life, he left Lincoln after a year and a half, seeking more of a social scene. Beny eventually graduated from West Virginia State College. He was in the Army for three years before returning home after being injured in a car accident. He used his military benefits to attend the University of Heidelberg in Germany for medical school and eventually finished at the University of Geneva, receiving his medical degree in 1959. Primm returned to New York and worked as a general practitioner while doing his residency in anesthesiology. He would often take his daughters along with him on his home visits with patients. When Jeanine Primm was a small child, her father would drive her and her sisters through the streets of Harlem in his Lincoln Continental after his shift at Harlem Hospital. It was during the height of the heroin epidemic in the late 60s. Through the window she could see men with their heads almost touching the ground, their eyes closed and their swollen limbs resting heavily like logs. “From that early age we could see what kinds of drugs were decimating the community, and he made sure we knew that,” remembers Jeanine. “He convinced the city to open up one of the first drug treatment facilities. He was pretty much a renegade back then. That was a big deal for a Black doctor.” Primm soon realized, however, that he was only treating the symptoms to more serious underlying problems. In response, in 1969, Primm helped found the Addiction and Research Treatment Corp., in Brooklyn, and has been the executive director ever since. He was a pioneer in linking addiction with infectious diseases, most notably AIDS, and approached treatment from a social perspective. At his treatment centers, addicts received help with housing, job training and, for those who were developmentally disabled, residential care — all new concepts at the time. Primm was even chosen by President Richard Nixon to go to Vietnam to survey the extent of heroin abuse by U.S. soldiers. Winston Price, president of the National Medical Association, says Primm was one of the first doctors to warn about the impact of heroin. “White America thought this was a Black problem in the slums of the city and if we simply turned our heads and avoided them they would kill themselves and overdose, but it wouldn’t affect us,” says Price, “It wasn’t until the early eighties, when heroin started to find itself in rural, suburban areas and outskirts of the city, that the outcry of ‘we need to stop the drugs from coming into the city and the country’ began to raise its head. But the Beny Primms of the day already knew that this was a problem that was going to affect everyone.” Today, Primm’s corporation has expanded into seven treatment centers — three in Brooklyn and four in Harlem. The centers serve an estimated 3,500 patients annually more than any other minority nonprofit community-based substance abuse treatment center in the country. In addition to the substance abuse centers, Primm operates four shelters for battered women in Brooklyn and Harlem. Primm also serves on the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, a commission of experts from different fields who advise the president on how to approach the AIDS epidemic. And recently Primm has been touring African American churches as well as schools with basketball-legend-turned-businessman Earvin “Magic” Johnson to talk about HIV/AIDS. Primm, who resides in New Rochelle. N.Y., says getting African Americans to seek treatment is a major obstacle and a large part of the disparities that exist in health care. “We don’t want to go to the doctor until it’s too late.” he says. “We think the Lord is going to help me. The Lord is going to take care of all my problems.” Big Sister Annelle Primm, 49, looks at her father with obvious affection as she prepares breakfast at her Baltimore home. She has embraced the role of caregiver for her family since her mother’s death from cancer when Annelle was 19 years old and a senior at Harvard University. She took a semester off from Harvard to accompany her mother on each of her visits to receive chemotherapy. The experience almost turned her away from the medical profession altogether. “I really didn’t want to come into contact with people who were dying,” says Annelle, who serves on the faculty at Johns Hopkins University (JHU) in Baltimore as an associate professor of psychiatry and an assistant professor of health policy and management. Still, she managed to finish out the year at Harvard and enroll at Howard University’s medical school the next year, with her sister Martine as an undergrad there and her sister Jeanine enrolled at a boarding school close by in Virginia. All three sisters still live in close proximity to one another in Baltimore. After receiving her medical degree from Howard, Annelle earned a master’s degree at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Public Health. During this time, she also had a fellowship at JHU’s School of Medicine in social and community psychiatry. One of the requirements of the program was to design an approach that would address the unmet needs of the minority community. So, in 1985, Annelle established COSTAR. The program was designed to provide specialized treatment for people with severe and persistent mental illness. Many of these patients were not receiving conventional outpatient treatment because they wouldn’t show up for appointments or take their medication. The COSTAR program consists of a team of psychiatrists, social workers and nurses who provide home outreach to minority patients with severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia. In addition to medical treatment, the team also makes sure patients take their medication and helps them with housing needs. The program was the first to implement such techniques in an urban setting. Though the program still exists, Annelle stepped down as director in 1995. “The way I think about mental health is an underpinning of a number of health issues. If mental health isn’t treated, some people will self-medicate with drugs. Once they start doing that, that opens them up or risk to STDs, like HIV/AIDS.” says Annelle. Annelle says she began to recognize how the mental health needs of Blacks were not being addressed. Depression would often go undetected and those who were diagnosed would not get the proper treatment. As a result, she developed two videotapes “Black and Blue: Depression in the African American Community and “Gray and Blue: Depression in Older People” to address the stigma in the Black community associated with seeking mental help. “I used the medium of video to level the playing field in terms of literacy.” says Annelle, who is also director of minority and national affairs for the American Psychiatric Association in Alexandria, Virginia. “In terms of educating people about mental health, we used people who had actually suffered from depression, so that it would come directly from them.” In 1994, Annelle met her husband Herbert Spencer, who is also in the health field. He works as a compliance officer for the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Spencer examines records and interviews physicians to make sure they are following government regulations. For example, if a medical provider is audited and it’s found that the provider submitted claims that weren’t documented, then the federal government could penalize the provider. But more importantly, the provider’s false claim could pose a great risk for patients. “If you have providers that aren’t doing the job and they are falsifying the documents, they’re contributing to health disparities,” says Spencer 47. On the Court Jeanine Primm is in an auditorium with a group of men who stare attentively as she prepares to give a lecture on sexual and health education. “So you and your boys are dressed, you’re going to the club, you look good, you smell good,” Jeanine, 41, says to her audience. In the background, the Isley Brothers are crooning seductively on the CD player— “I wanna keep you here layin’ next to me...” Jeanine pauses the CD with a remote control, “So you look around the room and you say to your boy.” Jeanine continues, as she switches to another CD and the voice of late rapper Biggie Smalls booms. “Cause I see some ladies tonight that should be having my...” “Baa—a—bay, baby!” all the guys yell in unison with Biggie. And Jeanine begins her talk about unwanted pregnancy at a rookie transition program where some of the world’s most beloved National Basketball Association (NBA) stars are nurtured. For the past six years, she has provided educational health services to the NBA Players Association, including lectures on domestic violence, sexual assault, parenting, STDs and HIV/AIDS education. Jeanine, who lives across the street from her sister Annelle, often uses hip- hop and other popular music to make her lectures culturally relevant to the players. “I think she does a great job with us in how she presents information,” says Purvis Short, director of player services for the NBA Players Association who played professionally for 12 years with the Golden State Warriors and Houston Rockets She makes it interactive, she accompanies it with music. The response from the players has been positive; they like the different approach.” Unlike her father and sister, Jeanine doesn’t have a medical degree, but she has always been involved in the health field. In the mid- l980s, she worked as a public health advisor in the Bronx. Jeanine would interview patients who had contracted sexually transmitted diseases to figure out who all of their partners had been. Then she attempted to find those partners and let them know they might have a disease. In the early ‘90s, Jeanine worked at an HIV counseling and testing program in Cambridge, Mass. It was there that she honed her skills at making presentations that appealed to the African American community. Jeanine hopes to one day take her “non Western” style of teaching that involves storytelling and music into high schools and colleges. A Family Affair Health Disparities Solutions was established after the Primm family realized the potential impact they could have on health care and the African American community when they combined all of their knowledge and expertise. “It was sort of a holiday dinner conversation that never seemed to get off the ground,” says Annelle. I finally said, “We need to do this.” Beny Primm is the president of HDS, Annelle is the vice president, Herbert Spencer and Jeanine are partners. Each family member brings a unique experience to the health care field, and organizations are taking note of their comprehensive approach. Last year, the Bay Area Addiction Research and Treatment Center in San Francisco contacted HDS for information on addiction in minority communities and its relation to mental health. Also in 2004, the company developed training and curricula linking mental health and chronic diseases for pharmaceutical companies interested in ethnic and cultural issues, Annelle says the goal of HDS is to become a nationally recognized company that provides high-quality consulting, educational services, training and expertise in the area of health disparities. The company hopes to provide strategies in addressing HIV and AIDS, substance abuse, policy and treatment, mental health diagnosis and treatment, as well as its impact on overall health, There is certainly a need for the services the Primms provide. Spencer points to the disparities in his own community, where Blacks in Baltimore city represent 90 percent of new AIDS cases. Nationally, the death rate for Blacks is 30 percent higher than for Whites. Forty percent of Black men die prematurely, while African American women continue to battle obesity, cancer and heart disease. Spencer says many of the problems are generational. “If some of those things could be corrected, then 20 to 30 years from now, we would have a different kind of landscape,” Spencer says of the health disparities. His sister-in-law agrees. “Disparities, health care. These are not just words. These are huge entities that keep thousands of people from getting the care they need.” says Jeanine. “But we talk about it just like it is another issue.” |