|

Black Soil: Interview with Fidel Castro |

|

|

|

City Paper Online, 2003 |

|

Feature

Black Soil

Maryland's African-American Farmers Hope a New Deal with Fidel Castro will Bring in the Long Green

It is a typical 80 degree day in Miami, and the one 45-minute flight

that leaves daily for Cuba is filled to its approximate 125-seat

capacity. Bags, sky blue plastic wrap securely swaddling each with

the names of the owners written in bold letters on the front, are

being loaded onto the plane. The process to get on this flight has

been an arduous one--with travel affidavits, visas, passports, and

detailed explantations as to visiting purposes along the way--and

the crowd is giddy and sometimes irrational with anticipation.

"I paid $400 for this ticket, and this man is in my seat!" one man reeking like a brewery and dressed in dark green army fatigues grunts loudly, though there is an empty seat in the same row next to his assigned seat. He opens his hands in indignation and admonishes the flight attendant for not acting fast enough in removing the offending party--John Boyd Jr.--because, as he sees it, "I paid for my seat." "Everyone on the flight has paid for their seat," the flight attendant reminds him, deviating from her plastic-smile routine with just a hint of disgust. This is Boyd's second trip to Cuba in recent months in his role as president of the lobbying group the National Black Farmers Association. In November, Baltimorean Kweisi Mfume, president of the national NAACP, hosted an 18-member delegation of NAACP members and a few NBFA members to the island, and during that time Boyd was introduced to representatives from the Cuban food import company, Alimport. Boyd asked Alimport representatives if they would be interested in doing business with black farmers, and they said yes. Now Boyd is taking a group of six National Black Farmers Association-affiliated farmers and lobbyists back to Cuba in hopes of finalizing an agreement with the Cuban government for the group's members to sell crops to the island. As the plane descends over Cuba, the surrounding terrain starts to come into focus. Beautiful fields are dotted sparsely with shrubbery, tiny homes, and a few skinny roads. There are buildings with roofs completely torn off and trees completely stripped of branches--evidence of Hurricane Michelle, which rocked the island with 135 mph winds in November 2001. The excitement builds as the American farmers realize they are about to enter taboo territory and the exiled Cubans on board--who are allowed to make this trip only once a year--are about to meet family members, many for the first time. "El Otro!" one man cries--referring to the "other" Cuba, rather than Little Havana in Miami. As the plane lands, braking crudely on the runway, the passengers hoot and clap loudly. Palm trees billow in the distance while Cubana airline planes sit expectantly on the runway of the Jose Marti La Habana airport. "Ahora!" the man who fought for his seat roars, raising one arm. The time is, indeed, "now" for those whom have had difficulty visiting this tropical nation just 90 miles from Key West, Fla., during the more than 40 years the United States has maintained its trade and travel embargoes against Cuba. Boyd rounds up his troops, heads toward a waiting area where passports and visas are checked, and ushers the National Black Farmers delegation to the curb where taxis and cars--ranging from more modern Japanese and European imports to vintage American Chevys and Dodges from the 1930s and '40s ones--cruise languidly. Several more recent Mercedes Benz models with yellow taxicab signs adorning their roofs also troll through the traffic .

Boyd is a fourth-generation farmer in Virginia, farming land paid for by sweat. Because some whites still refused to pay blacks for their labor after slavery ended, they would often pay them with land--usually land that was hilly and unsuitable for growing. Boyd says that his great-great grandfather was given land that white slaveowners did not want after he was freed from slavery. "What they didn't realize was that it was very valuable land," Boyd says. He still owns the farm, around Lake Gaston in Mecklenburg County, Va. Boyd was the impetus behind the victorious 1999 class-action suit spurred as a result of institutional discrimination on behalf of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Even now, Boyd says he was shocked when he watched his application for a standard operating loan thrown in the trash can during an interview with a USDA official in 1989. When he wasn't given a satisfactory explanation why his loan was denied, Boyd decided to fight back. "At first, I thought it was just a schism between me and the loan officer," he remembers. "But it turned out he was treating other black farmers in the area the same way. He would tell me, 'Why don't you just sell, and we will find a place for you and your family to live.' They were really after my property." An uncooperative relationship with the USDA is a serious issue for any farmer. The USDA is a major source of farm loans and subsidies--loans that farmers need to get their crops planted and subsidies that help shore up their operations during bad growing seasons. Access to timely loans is vital, particularly to those who run small farms, as many black farmers do; according to press reports, black-owned farms average about 50 acres. In 1984 and 1985, the USDA lent $1.3 billion to farmers nationwide to buy land. Of the nearly 16,000 farmers who received those funds, only 209 were black, according to a Sept., 2000, Washington Times article. In the mid-'90s, Boyd started holding meetings at his house with other black farmers. By then, some of the farmers had already lost their farms to foreclosure. Soon, Boyd recalls, "they started moving into my house. By 1995, I had seven [black] farmers living in my house that had lost their farms." In 1996, Boyd and around 100 other farmers held their first protest at the White House with a tractor and a mule in tow. This along with subsequent protests garnered major media attention and mobilized farmers. "I can't tell you how many times I have been to jail for these peaceful protests," Boyd says, though he estimates the number at about nine. Eventually Boyd and his fellow farmers' activism led to the class-action suit in 1999. But the class-action victory didn't level the field for black farmers as hoped. According to Washington Post reports, even though the USDA admitted that black farmers had been collectively discriminated against, unlike any other group victorious in a class-action suit, they were still required to individually prove discrimination. This required them to prove that a white neighbor received a loan and they did not. About 13,000 black farmers have been able to prove this so far; each were given lump sums of $50,000. But about 50,000 cases were rejected--partly because they did not have access to their white neighbors financial records. (Few farmers of any race keep such detailed records.) There are still about 20,000 cases pending. Blacks farmers are facing extinction. They now make up less than 1 percent of the nation's 1.9 million farmers, and their numbers declined by 43 percent between 1981 and 1996--the time period the lawsuit covers. In addition to the rampant foreclosures, many farmers have simply given up on their farms and sought careers elsewhere. A lack of interest in farming in the younger generation has also led to a loss for both white and black farmers. But black farmers have also continued to suffer without the help of government subsidies, which often go to larger, wealthier farming operations. Thanks to Cuba's communist economy, Alimport purchases food for the entire country--from restaurant and hotel kitchens to individual holders of ration cards. There are no corporate fast-food restaurants or big chain grocery stores, though there are small bodegas and vegetable and fruit stands. Usually when American farmers sell their produce in other countries, they face a highly competitive market. Selling produce to Cuba--with no middlemen taking a cut, no competition--would be good and steady market for U.S. black farmers, to the tune of about $12 million a year, according to Boyd. "We have been trying to do business with other countries for a long time, to become independent from the federal government," Boyd says, because "the federal government has shown us historically that they don't want to do business with us." If the deal Boyd is in Cuba to negotiate goes through, the plan is to divide the payment among several thousand black farmers, he says. And the deal is open to any of them who want to participate, not just to National Black Farmers members. Just as important, Boyd says, a deal like this will help bolster the farmers' credit ratings to secure bank loans for the next year's crop. Cubans would profit by receiving commodities--like the national staple, rice, which they currently buy from China--at a much lower rate because of the cheaper transportation costs. In addition, the Cuban government has routinely reached out to marginalized communities: Thousands of Cuban doctors consistently volunteer throughout Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and the government has offered 500 scholarships to Havana's world-renowned Latin American School of Medical Services for low-income people of color around the world. In many ways, the Cuban government's negotiations with the National Black Farmers is another supportive gesture to a struggling group. Congress passed a law in 2000 that allows Cuba to purchase food and medicine from U.S. producers as long as it pays in cash. Since Cuba started taking advantage of the law a year ago, it has purchased about $189 million worth of American food with cash, mostly from large agricultural businesses, according to an Associated Press report. The law, however, prohibits Cubans from buying crops that have been grown with the aid of U.S. federal subsidies. For whatever reason, many American black farmers make do without federal money. They are looking for new markets for their produce, and Cuba is an attractive one on several levels.

On the second day of its trip, the group from the National Black Farmers Association visits a tobacco cooperative in Cuba's San Antonio de los Banos region and meets with members of Alimport to discuss the details of negotiations. On the ride out to the farm, members of the delegation look out of the windows of their bus at civilians riding on scooters flanked by family members in ancient sidecars. On this sunny day, there is little evidence of the torrential downpours that engulfed the city the night before, with resulting blackouts and water so high it washed over curbs and completely covered tires of cars. The unseasonal rain caused many of Cuba's antique American cars to stall, and many drivers were pushing their vehicles in the downpours along the blackened streets. Billboards line the route out of Havana and toward the farm--defendiendo el socialismo (Defend socialism), revolucionar anti imperialista (Revolution against imperialism), una sola decision, patria o muerte (One decision, my homeland or death), revolucion es unidad y independencia (Revolution is unity and independence)--lecturing weary workers. As the farms start to come into view, green bananas hang from trees in the shape of pine cones and heavy stalks boast plump sweet melons. Cows and goats wander over the fields, grazing them clear of dead and rotten crops. The tobacco farm the National Black Farmers group visits today is where leaves that wrap world-famous Cuban cigars are grown. Oxen yoked together with a stiff piece of board till the land to keep the red clay-like earth soft. It is moist and cool under a vast tarp that shades the man-sized leaves so they won't be overexposed to the sun. During harvest these leaves are picked one by one, by about 4,000 workers. There is little modern machinery used. Even grass is still cut with a machete. Cuban agriculture would take advantage of more modern methods if it had access to them. But it has had to adapt to privation and its isolation from the mainstream of modern technology. And things are, in some ways, even less advanced than they were 20 years ago. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, long communist Cuba's foremost patron, imports of pesticides and fertilizers fell by 80 percent, so Cuban farmers have had to use biological controls--like crop rotation every three years--to maintain the soil. "During the time that we are not growing tobacco, we use crops that will benefit the soil, like bananas and cassavas," says Walfrido Hernandez, general director of the Tabacalera Lazaro Pena farm. He contends this is the reason the Cuban cigar is highly sought after all over the world. Even after the 2000 law enabling Cuba to buy food and medicine from the United States was enacted, the Cuban government initially refused, insulted by restrictions that allowed for exports to the country to be paid for only in cash and the continuing refusal to allow Cuban imports. After slow-moving Hurricane Michelle hung over the island for a week in November 2001, the United States relaxed some of the more Byzantine restrictions and hurdles and agreed to sell Cuba wheat, rice, corn, and poultry. This was shortly after Sept. 11, 2001, immediately after which the Cuban government opened its air space to U.S. planes rerouted by the terrorist disasters, granting permission to circle the island and land at Cuban airports. On Sept. 15, President Fidel Castro even led a rally dedicated to condemning the attacks and showing solidarity with the U.S. people. The Cuban government still rankles under the trade restrictions imposed by the United States. But the economic value of trading with the island's nearest sizable neighbor is too great to resist. Since then, the Cuban government has hosted many U.S. delegations visiting its farms--and has made several agreements with several U.S. farm groups to buy agricultural exports. White farmers are losing numbers as well, and have seen Cuba as a new international market for their produce too. Last December, Kansas Farm Bureau president Steve Baccus took an 11-member delegation to the island. "Opening new international markets for Kansas-produced commodities is vital for the long-term success of our farmers and ranchers," he says. American Farm Bureau Federation president Bob Stallman led a weeklong trip the month before the Kansas delegation arrived, leading to to a deal to sell $200 million worth of products to Cuba by this spring. But even with these piecemeal deals, U.S. farmers have lobbied Congress saying that the embargo costs them $1.24 billion annually, according to a report put out by the Washington-based Cuba Policy Foundation. Still, while trading in U.S. exports has been opened, there are still many barriers to making it a smooth process. There are miles of U.S. red tape to navigate: special licenses to travel to Cuba, licenses for getting the products to Cuba, licenses for getting the payments from Cuba, and licenses for the shipping vessels. "We lose money in every transaction," says Maria de la Luz B' Hamel, the Cuban minister of commerce. "But still it is less expensive than getting what we need from countries farther away."

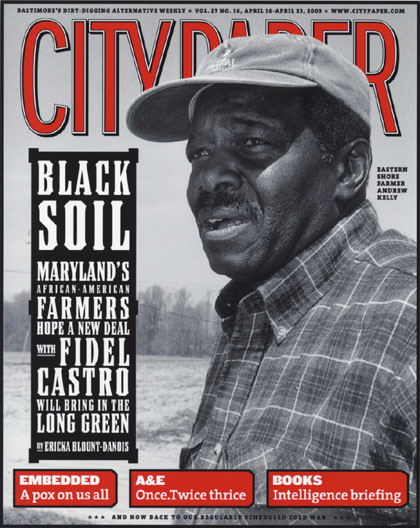

Andrew Kelly's farm has been in his family since 1938, when it was just an old rundown, tree-studded piece of land in Bethlehem, on Maryland's Eastern Shore. His parents bought it from the doctors they worked for. They cleared the land with just one horse and one mule. Kelly, who still farms his 125 acres full-time at age 65, says that depending on the price per bushel he could get selling his produce, the Cuba deal sounds like a good opportunity for him. He has been waiting for two years for an answer to an affidavit he filed against the USDA with the class-action suit. Right now he produces mostly for Asian markets--hot peppers, yellow stars, string beans, and lettuce that he sells to Korean and Chinese grocers in New York, Washington, and North Carolina, and to Butcher's Wholesale on Howard Street in Baltimore. He drives his own 22-foot truck, spending most of the week on the road delivering his produce. Since Kelly operates on a small scale, he has to cater to very specific needs. He can't compete with farmers and agricultural businesses that grow mainstream produce for Giant or Safeway, which is why he specializes in the Asian market. (He says he couldn't sell his current crops to Giant or Safeway even if he wanted to, because he often produces more of his specialty items than the big grocery chains would want to buy.) But working without the stability of a corporate buyer can sometimes be trying, not to mention dangerous. Each time Kelly delivers, it is to a different person. He says that after one long delivery drive to New York, he was robbed and beat up by the grocers to whom he intended to sell his vegetables. "They beat me up pretty bad and broke my leg in several places," Kelly says. They also stole all of his produce. There are other, more traditional risks to farming. Last year Kelly lost a lot of money as a result of the drought. This year he is looking to make that money back. "I would be very interested in a business deal like the Cuba one," he says. Kelly is not a member of the National Black Farmers, but Boyd says if the deal is finalized it will benefit approximately 10,000 black farmers, many of whom are in the South and already growing the crops that Cuba needs. "The deal is open to any black farmer who can grow the crops," Boyd says. "My idea was to get a long-term commitment from the Cuban government and not just a one-shot deal. A long-term commitment would make a significant difference in the life of the black farmer." Boyd says that farmers will bring their products to regional buying stations and sell at a price agreed upon by the Cuban government. Buyers at the stations will then drive the goods to ports where it will be shipped to Cuba en masse. "With this deal we would cut out the middleman--right now farmers go to buying stations like [an ADM grainery] and sell their product at the going rate, the buyer then sends it to other countries," says Chris Ray, a lobbyist and member of the National Black Farmers Association. "We would have a guaranteed price under the Cuban contract. We would go straight to the supplier, which would be a financial gain." But the complex problems of black farmers may not be so easily addressed by delving into international markets, in part because not all black farmers face the same problems. Off of a small dirt road in Preston, on Maryland's Eastern Shore, part-time farmers Paulette Greene and partner Donna Dear have been farming a little more than 100 acres of farmland since 1994, growing grains, vegetables, and fruit. A tractor sits lonely in the midst of the wide, reaching, flat land. It looks dusty, ancient, and unused. Greene, a native New Yorker, inherited this farm from her family and originally had not planned to farm on it, but rather was just looking for an investment. Nonetheless, "we always had a garden, so we thought we would just try it on a larger scale," Dear says. Greene and Dear now sell their produce to local markets (including truckloads of watermelons to Korean grocers in Lexington Market) and "hucksters"--people who sell their produce on the street in the community, à la Baltimore's arabbers. "We are trying to find one single niche," Greene says. "I have learned not to grow more than what we have contracts for." The USDA gave Greene and Dear a loan in 1999 to pay for operating expenses and farm equipment. But because of bad weather--in addition to problems they experienced with a fertilizing company that gave them substandard service, wasting time and money during a critical part of the growing season--they were not able to start growing until 2000. Now they are in negotiations with the USDA to prevent the agency from seizing their equipment. "They want to take 60 acres of our farm," which Greene says was their collateral. She adds she is already looking for other work and other business ventures. Greene says a business deal like the one the National Black Farmers is negotiating with the Cuban government probably wouldn't do much to benefit the average black farmer who is pitching pennies with small operations. "A deal like that wouldn't help us because we don't have the money to pay for the equipment to grow the crops that Cuba needs," says Greene, who is not a part of the USDA class-action suit. "We need seeds, we need equipment. It costs to grow it, to cut it, and to ship it. Will there be grants or loans to help us? A lot of black farmers might not get involved, because they will be skeptical."

By the final day of the National Black Farmers delegation's trip, the farmers and lobbyists have visited an agricultural high school, met briefly with the minister of commerce, and spent some free time wandering the island. But no final deals have been made, no paperwork signed. Nada. The flight back to Miami leaves at 4 p.m. and it is already 11 a.m. They need to be at the airport two hours in advance to clear security and declare items. "Things are looking pretty bleak," admits Garriell Lambert, a Virginia tobacco farmer. What he and most of the rest of group don't know is that Boyd has already begun to finalize plans with Igor Montero Brito, president and chief operating officer of Alimport. At 11:30, the National Black Farmers delegates are loaded onto a bus to take them to the offices of Alimport. Here they agree to sign a letter of intent to supply Cuba with tens of thousands of tons on corn, wheat, soybeans, rice, and chicken each quarter, a deal worth $6.4 million. If the agreement goes through, the first shipment of 10,000 metric tons of corn will be due by the end of May. At noon, with time to get to the airport getting ever shorter, the members of the NBFA group load back onto the bus and follow members of Alimport to a new destination. When they reach the anonymous building and pass security checkpoints, they are told El Comandante is waiting to meet them. The delegation is nervously silent. As the elevator doors open, he is waiting there, complete with his standard attire of army fatigues and black sneakers. There are no bodyguards, no cameramen--not even the makings of an entourage. Just him and his interpreter. It is as casual an encounter as meeting a friend for drinks at TGI Friday's. At 76, Fidel Castro is still the picture of health, still the same as the familiar images from U.S. television. With the exception of a few age spots on his hands and forehead, it is difficult to tell he has grown older. His voice is strong as he greets everyone warmly and sits down with his rum-laden mojito--the national drink of Cuba--to get to know his visitors better. He has given up smoking cigars, he says through his translator, after the Cuban government began its campaign against smoking. "But then, everyone has the right to commit suicide," he adds with a laugh and a mischievous twinkle in his eye. El Comandante's black digital watch reads 1:04. But no one is pressed for time now. He touches Boyd on the hand and says, "I see that it has not been a useless trip. You have made progress, and I am glad to hear that." Lambert tells Castro that he remembers going with his father as a 5-year-old to see the Cuban leader in Harlem. It was during a historic visit Castro made to the United Nations in 1960, right after the victory of his revolution and after Cuba nationalized all formerly U.S.-owned banks, utilities, and other industries. Although he was booked at the Hotel Shelbourne in midtown Manhattan, Castro was asked to leave because the owner worried about adverse publicity. The black owner of the Hotel Theresa in Harlem offered him free accommodations. It was here that Castro met with Malcolm X and hosted meetings with leaders from around the world, including President Gamal Abdel-Nasser of Egypt, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India, and Nikita Khrushchev from the Soviet Union. "You were very young, but also must have been very smart to leave New York City and work the land," Castro says teasingly, pointing his finger at Lambert. "I think with every passing day people will be missing the quiet of the countryside. It is good to see a real farmer in your group." There are actually only two farmers in the group of six--the rest are lobbyists, assistants, and researchers, although all are members of the National Black Farmers Association. More seriously, Castro says, "It is good that there are still some [farmers] left. The advantage of the U.S. is your great productivity, especially with the soybean." And the potential perils of global warming come up, too: "We are in the midst of the harvest, and all of a sudden we had these summer rains--at any moment you could be growing sugar in your Southern states with all of these climactic changes." Castro listens intently with his head held to the side as everyone introduces themselves. He talks with each person before announcing that he is very hungry and is ready for his guests to eat lunch with him. "It would have hurt me if you had left and I had not had the chance to meet you," he says. As everyone sits down at a table in the parlor, Castro asks what careers blacks in the Southern states pursue. "Those that can afford it go to college," Boyd begins. "Exactly, that is a major issue," Castro says. "A lot of them look at technical careers," Boyd says. "Even in our country where we have 90 percent literacy and semiliteracy, with the passage of time, we realize it is not enough to simply give everyone the same opportunity, because some people come from so far behind," he says, touching his hand to his forehead and pointing his finger to make his point. "It comes from social status. Children with parents that are professors will continue to make it to the elite schools. Now we have programs to try to alleviate this. "I am very glad of the results of this visit," he says, dipping into his large plate of French fries. "We have many visitors here--sometimes it is not easy to meet everyone, but we have our priorities. I remember the fine meeting we had before, so I am very happy that you have your letter of intent. The young man that talks about my visit to Harlem, there is that sentiment that brings us together," says Castro, alluding to Cuba's active kinship with marginalized communities around the globe. "It is more than trade, it is friendship. "We can help introduce you to Third World markets," he continues. "There are people who need to buy lots of food in the Caribbean and Africa." "We would appreciate advice or help with that," Boyd says. "We would be happy to know these countries." It is 3:30 by the time everyone is finished with lunch. On the mad rush to get everyone to the airport, most members of the National Black Farmers delegation are elated and anxious to boast to family members and friends back home. Lydia English, their translator, sits somewhat stunned. "I can't believe that just happened," she says. But as reality sets in back in the States, even with a deal brokered, there are many ifs remaining. There are a host of barriers to a successful completion of this deal--extensive permits, organizing thousands of farmers, and having weather that permits production of good crops. Down on the Eastern Shore, Kelly hopes the deal with Cuba becomes a reality for him and his small operation. "I just want an equal opportunity to farm and be as productive as everybody else," he says, pausing to think about the possibilities. With a laugh, he adds, "I could probably give them more than they could use."

|